Why do I describe my career on an adventure blog. First, the job itself was quite the adventure, and it inspired many other adventures through the travel it led to and the people I met. In describing my adventurous pursuits on this site, omitting my thirty years with Schlumberger would be a big hole. Second, our children are thinking about their future careers, with Bailey in an internship and Samuel wanting to go overseas with work. It might be of interest to them or others seeking adventure. Underlying this is my desire to write down what I can remember. The vividness of the memories I have from decades ago amazes me, especially at the beginning of those thirty years. I remember some things, but others are blank. Each photo has a story. I probably write primarily for myself, but if you wish to join me on any part of this memory, you are welcome!

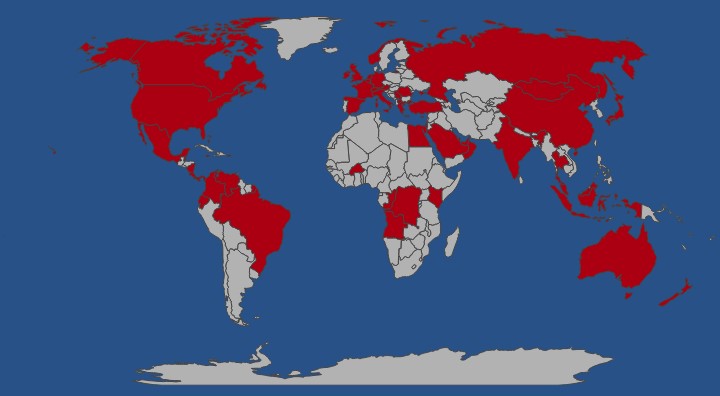

In short, I held 11 jobs in 16 locations in 8 countries and visited many more across six continents. However, it was the continuous interaction with people from all over the world that really brought the adventure. This included meeting my wife and moving my “home,” though the concept of where home is continues to challenge me!

I am thankful for the amazing experiences that the hundreds of Schlumberger people that I interacted with provided and made this journey such fun. In this post, I have mentioned those people that my memory and photos remind me of and I apologize for omissions. If you are omitted or have memories of our time together, please share and I can add them!

As well as working with so many remarkable people, Schlumberger enabled me to participate in the usage or development of the most remarkable technologies. The diversity of roles I took on supplemented the adventure, and my career trajectory had four “resets” where I transferred laterally to do something completely different (from Operations to Software Development to Managing Acquired Companies to Quality Management to IT Portfolio Managment).

| Dates | Job | Home base | Countries visited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1991 | Before SLB | Chorleywood, Lincoln, and Cambridge in England | England, Scotland, Wales, Malta, France, Monaco, Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Vatican City, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Greece, Yugoslavia (now North Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, Croatia), Jersey, Egypt, Venezuela, St Lucia |

| 1991 – 1994 | Wireline Field Engineer | Fahud in Oman, Amriya in Egypt, and Marmul in Oman | UAE, Egypt, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Cyprus, Kenya, Russia, India, Thailand, Indonesia, Bermuda, Australia |

| 1994 – 1995 | Wireline Field Engineer | Aberdeen in Scotland | Ireland, Spain, Bermuda, England, USA, Belize |

| 1995 – 1997 | Anadrill Field Engineer | Lafayette in LA, Houston in TX, and 3 months on a drillship | Ecuador, Panama, Barbados, Cayman Islands, England |

| 1997 – 1998 | Anadrill Technical Manager | Pointe Noire in Congo, and Luanda and Soyo in Angola | Angola, Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burkina Faso, Costa Rica, England, USA |

| 1998 – 2000 | SPC Data Quality Engineer | Sugar Land in TX | Canada, England, Scotland, |

| 2000 – 2005 | Horizon Project Manager | Austin in TX | England, Netherlands, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, India, China, Japan, Nicaragua, Jamaica |

| 2005 – 2006 | QA Manager | Beijing in China | England, USA, Korea |

| 2006 – 2010 | Sensa Sustaining Manager | Southampton in England | Canada, France, USA |

| 2010 – 2011 | Diamould General Manager | Barrow-in-Furness in England | Brazil, Northern Ireland, Isle of Man, USA |

| 2011 – 2015 | Completions Quality Manager | Rosharon in TX | Mexico, Canada, Northern Ireland, Scotland, England, France, Norway, Saudi Arabia, China |

| 2015 – 2021 | Technology IT Portfolio Manager | Houston in TX | India, Ecuador, Colombia, Mexico, Canada, Northern Ireland, Scotland, England, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Norway, Cyprus, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Malaysia, China, Turkey, Israel, British Virgin Islands |

Applying to Schlumberger

My parents had met working in Nigeria and returned to England before I was born. Some of our family holidays were “on the continent” in France, Spain, or Portugal. During my year “off” that I took in industry between high school and university, I twice travelled around Europe by train with friends, visiting most of the Western European countries, and it gave me the bug. I spent most of that year “off” working at Ruston Gas Turbines in Lincoln, England, where they provided structured training for their “sponsored students,” hoping to employ them as graduates. That training was excellent learning, but it strengthened my desire to travel and do something exciting. Rustons had a commissioning department which installed their gas turbines around the world, often on oil rigs, so I tried to get a placement in that department, but they were not interested. The previous year’s intake of sponsored students included Jim Andrews who stayed for six years before moving to Schlumberger.

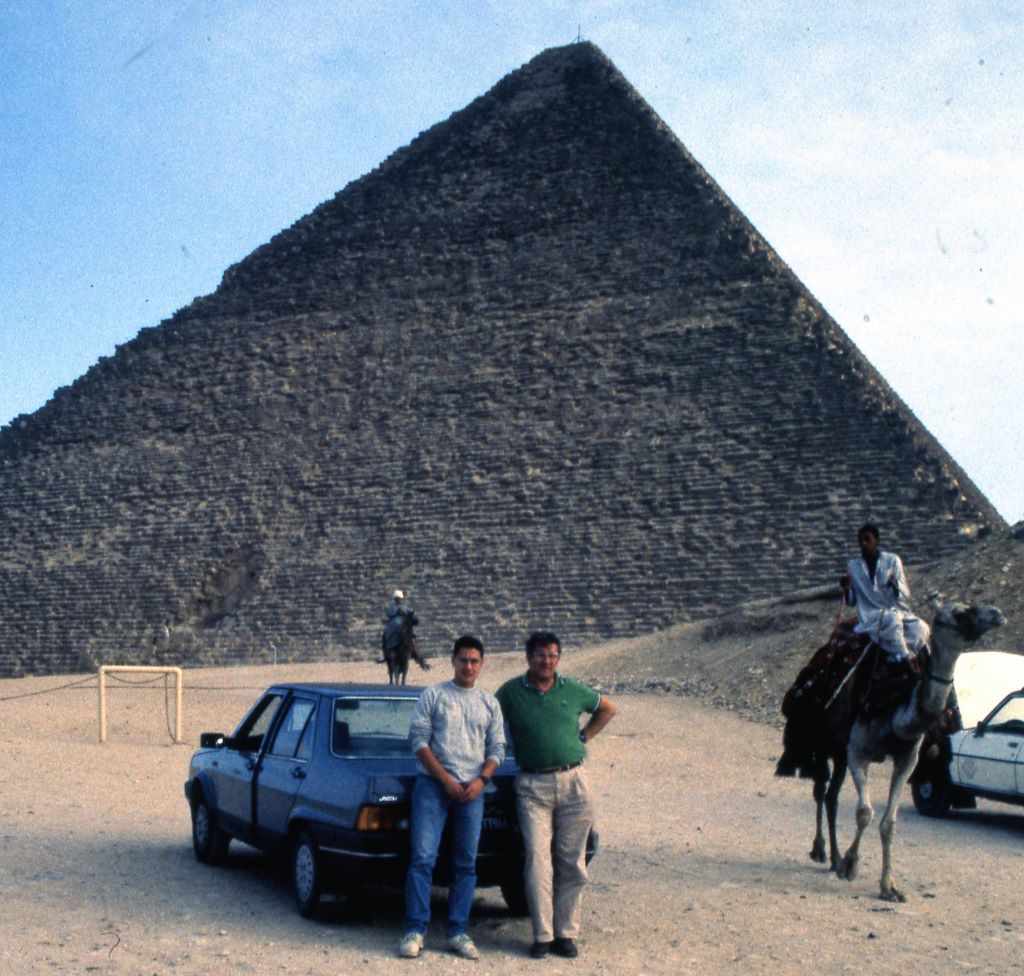

During my second year (of three) studying Engineering at university, a friend (Francis Boundy) suggested I apply to be a Wireline Field Engineer with Schlumberger. I had only heard of the company in our fundraising efforts for our SCUBA diving expedition to Egypt in 1989 when I had written to the Schlumberger office in Egypt asking for donations and my letter went unanswered. To prepare for the interview, I researched as best as I could in the career centre library (this was 1989 so before the internet). I remember the application form needed a passport photo, and the only machine I knew of was at the train station, so I cycled out there in my jacket, tie, and shorts. My first interview was at Schlumberger’s Cambridge Research facility, in the same city as my university. It was an impressive facility leading the research in the oil and gas domain and I immediately thought how I could help form a “bridge” between the PhD experts and practical experience. All that I remember from my second interview in Aberdeen was a “test” where I had to assemble a Baker Setting Tool (BST), that I knew nothing about at the time, based on a drawing. The trick was that there was a piece that fitted in two different ways, but only one was correct. I also remember how the recruiter told us that he joined Schlumberger so he would not have to wear a suit, and that he now wore one daily! Schlumberger offered me a job and it was up to me to tell them when I could start. The only other job I applied for was with BP, who also offered me a job. Of the twenty or so people I interacted with in their interview, half were from Schlumberger and advised me to start there, as I was open about the offer they had given me. The others who were advising me against Schlumberger were describing harsh work conditions, tremendous physical and technical challenges without sleep, and the instability of working anywhere at any time. It was these “negative” descriptions of Schlumberger that convinced me that is what I wanted to do! However, I was thinking that Schlumberger would be more “fun” than a serious career, so after a few years of experience, my plan was to move to BP, like all the people I had met.

Between Graduation and My Schlumberger Start

I graduated in May 1990 and headed to Venezuela in October with an expedition. The Schlumberger recruiter, after I had told him that I would be ready to start in March 1991, replied that they would be in touch closer to the time. I had no idea where in the world they would send me. Knowing I was joining Schlumberger, we visited a location in Anaco where Martin Vann was manager, and we learned early that they worked hard and played hard. An engineer, who looked like he had not slept for two days, took us to a rig, which was fascinating while the local practices were terrifying. The following day, it was a weekend, so we joined a boat trip out of Puerto La Cruz for a barbecue on an island. We had tried to visit the office in Caracas, but everyone had seemed too busy.

In November, we were living in a remote village’s school in Northeast Venezuela. The BBC World Service kept us informed of football results and of Margaret Thatcher’s resignation. I checked in with my parents and my Mum spoken with the Schlumberger recruiter. Unexpectedly, they had offered me a choice: Middle East or Morecambe Bay. I think the “choice” was because the first gulf war had started in August 1990. However, Morecambe Bay is a location that serves a gas field in Lancashire, England, very close to where my Mum grew up, and she let the recruiter know that I had not joined such a company to go and work in Morecambe! While going to a war zone was uncomfortable, I felt confident a large company would look after its people. We completed our expedition, and I trekked up the Auyan Tepui in February. That trek was an “out and back,” and I remember the significance of the turnaround point, with my life trajectory changing to my future career path.

This was my life’s turning point. The destination of our out-and-back trek represented when I started my journey towards a career.

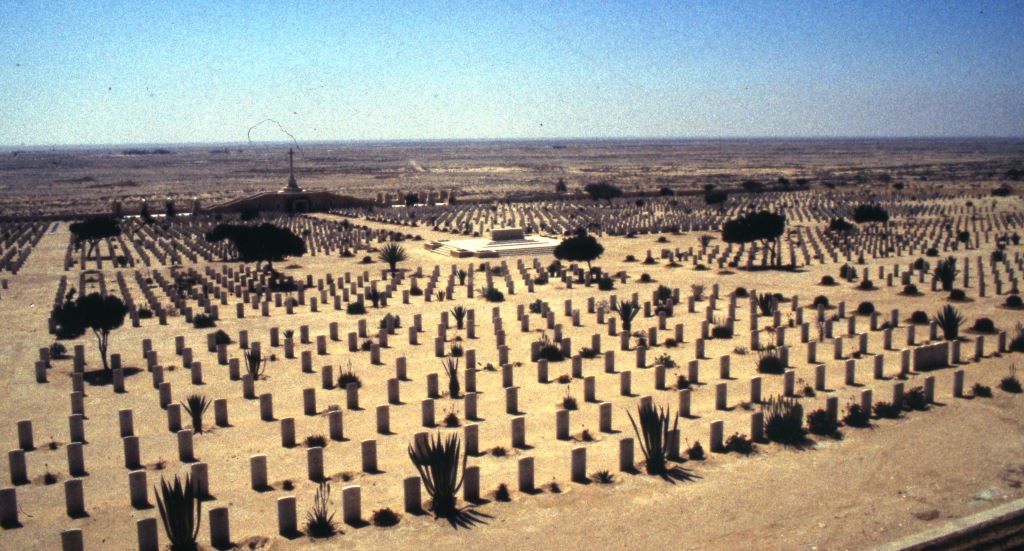

March 1991: Dubai, UAE

The first gulf war had ended at the end of February, and I flew to Dubai in the middle of March with my one suitcase to sign my contract and for induction with my “class.” The Schlumberger office was in the World Trade Center, the only skyscraper at the time in Dubai, and we stayed next door at the Hilton. We were the eighteen engineers who made up “ETC-35,” the thirty-fifth school at the Egypt Training Center that we would attend soon. While the gulf war was over, it felt very close. We played beach volleyball at the Hilton Beach Club with US marines on R&R. There was smoke in the sky from burning oilwells in Kuwait. One member of the class, Mark Balen, was transferring from another division and had been at the base in Saudi Arabia when a SCUD missile landed next door. We learned of the tragic accident when a truck drove into a burning oil slick in Kuwait. I was glad that Egypt, where I would be training, and Oman, where I would be working, were far away from Kuwait and Iraq.

April 1991: Fahud, Oman

Next was a one-month assignment called “pre-school” where one worked at a field base, shadowing various people to get an appreciation of what the job was. Schlumberger had a location in Fahud, a small oilfield town about an hour’s drive across the desert or a short flight from Muscat. I remember the base manager was Khem Kensuik-Mengrai from Thailand. I was impressed by the operations manager, Marwan Moufarrej, who had driven an ambulance during the war in his hometown of Beirut, managed all the local staff. While there was a strong push to hire local engineers, the Omani educational infrastructure was still catching up and there were several other British engineers, perhaps because the main client was Shell. There were maybe ten Field Engineers and morale was pretty low because everyone was worked so hard in a remote desert location. It seemed like everyone would leave within six months, and I think most did within two years. I learned a lot in that month.

At this time, email was barely a thing, and we used something called “Vax Mail,” allowing messages between computers. James Mead, my best friend in college, had joined the British Antarctic Survey and was based in Antartica for 2.5 years continuously at this time, frozen in during the winter. After months of trying, James and I worked out how to send emails to each other. At the time, it was probably the biggest temperature difference that two emails were sent between!

I certainly felt a long way away from Southern England, but that was OK!

May to July 1991: Amriya, Egypt

The training school was presented as the final step of recruitment, and not everyone was expected to make it. Eighteen of us started at the Egypt Training Center which was located in a small town called Amriya on the outskirts of Alexandria in Egypt. It included challenging technical learning, complex practical skills, and “intensive” tests that lasted twenty-four hours. Five of the eighteen did not finish and were sent home. We worked hard and played harder, as best as we could in a remote part of Egypt!

Back row: Me (British), Amr Hussein (Egyptian), Sulaiman Al-Ghashim (Saudi Arabian), Mark Balen (Canadian), Zafer Sakka (Syrian), Vincent Boardmann (French), Georges Elzir (ETC Manager from Lebanon), Tejinder Singh (India).

Front row: Adrian Turner (Australian), Dominique Besson (French), Mohammad Al-Shayeji (Kuwaiti), Sameh Asaad (Egyptian), Ahmed Al Adawi (Egyptian), Francesco de Lucia Daffolo (Venezuelan), Jose Astolfi (Instructor from Argentina).

Playing squash was normally a great stress relief, and I remember Amr and Sameh being very good and I would have hard-fought competitive games with Dominique. In one game, which I am sure I was winning, Dominique’s follow-through hit my eye hard. With Amr’s help, we managed to find a doctor in Alexandria who stitched up above my eye and fortunately the eye was fine. Before the doctor poured some anesthetic over the wound and into my eye to help with the stitching, I was unable to explain that I was still wearing a contact lens! When the cut had healed, I removed the stitches myself.

August 1991 to March 1994: Marmul, Oman.

Instead of returning to Fahud, I returned to its sister location, Marmul. Marmul is in South Oman, further away from Muscat which made it more isolated. My first priority was to “break out” so that I could start running my own jobs and earn bonus. John McBeath was my assigned tutor and he wisely steered me to run jobs independently. I remember his heartfelt advice to take something away from these experiences, ideally some savings! John resigned shortly after I broke out, but it was fun visiting him and his wife in their new home in Wimberly, Texas, when I was training in Houston in 1995. After several months working with John, I broke out and ran my own jobs throughout Oman. Our work schedule was typically three months on (7 days a week), 3 weeks off, with a two-month long vacation at the end of each year. It was intense and many burnt out, but the experience is unforgettable while difficult to describe.

John would play More Than Words by Extreme on the tape player and we would sing along as loudly as we could.

Shortly after I broke out, John let me know that he would not be coming back as he was resigning. A lot of that happened.

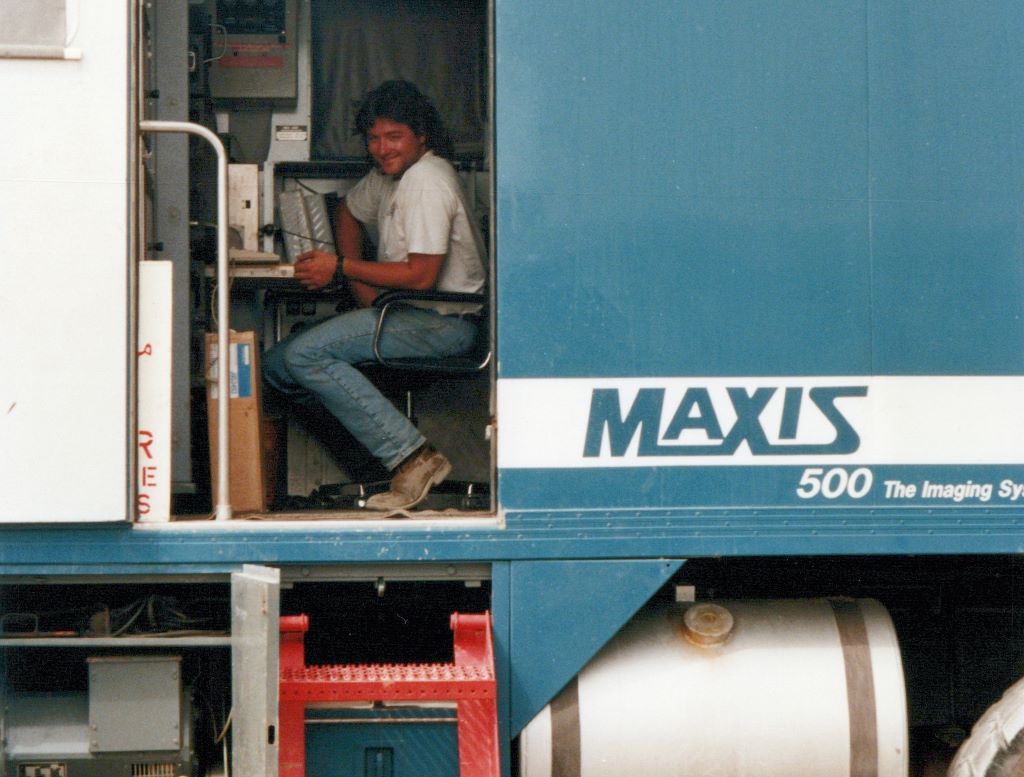

At one point, I was very frustrated with the way new software was being distributed for the new MAXIS system. I shared an email to local management and copied a couple of other people. This was early days of email and I quickly learned that copying people up the chain was not the way to impress people! The local manager, John Amedick, whom I had inadventently thrown under a bus, advised me that friends last a long time, but enemies last forever. He was gracious and this was an early correction to my hotheadedness. It was a valuable early lesson in email etiquette.

I remember one particular job when I was on loan to Fahud. I was briefed by the location manager, Sami Iskander (who has since been COO of British Gas, among other things). I ran some particular equipment that no one else in country would know about (MSCT) so I was completely on my own. Fortunately, the job went very well, which was extremely satisfying.

The teams of operators were either Omani or Tanzanian. Oman had a strong relationship with Tanzania. My crew were from Tanzania, speaking Swahili between themselves and Arabic to others. I was honored to be invited to one person’s home in Muscat where I enjoyed roast goat.

Other managers that I had in Marmul were Bertrand Campenon and Simon Farrant.

While we worked hard, the “junior” staff worked much harder. They were from Kerala in South India. They lived in cramped living conditions and had little time off, typically working two-years on and two-months off. They earned very little, but it was much more than they could get back home. On one of my days off, I went to visit their town. They had kids spaced two years apart, not even meeting the child until they were over a year old. One child had died falling into a water well.

We lived in what must be described as a luxurious camp. The same layout was used in Fahud. Irrigation systems fed the vegetation and we had a swimming pool, movie room, gym, game room, though life centred around the dining room and bar. There was a basketball game each evening, but my American colleagues were rather better at the game than I was. The centrepiece of our bar was a large propellor that the staff had rushed to salvage when a ship ran aground a few years beforehand. I took this set of photos when the Fahud camp burnt down, and they wanted to know what the camp had looked like.

Traveling to jobs took me all over Oman.

During my three years in Oman, it rained once for a couple of days. It was very dangerous for a time. Large lakes formed and this one, by our camp, remained for six months afterwards.

I spent a lot of time in this desert, and managed to get a few arty photos in between jobs!

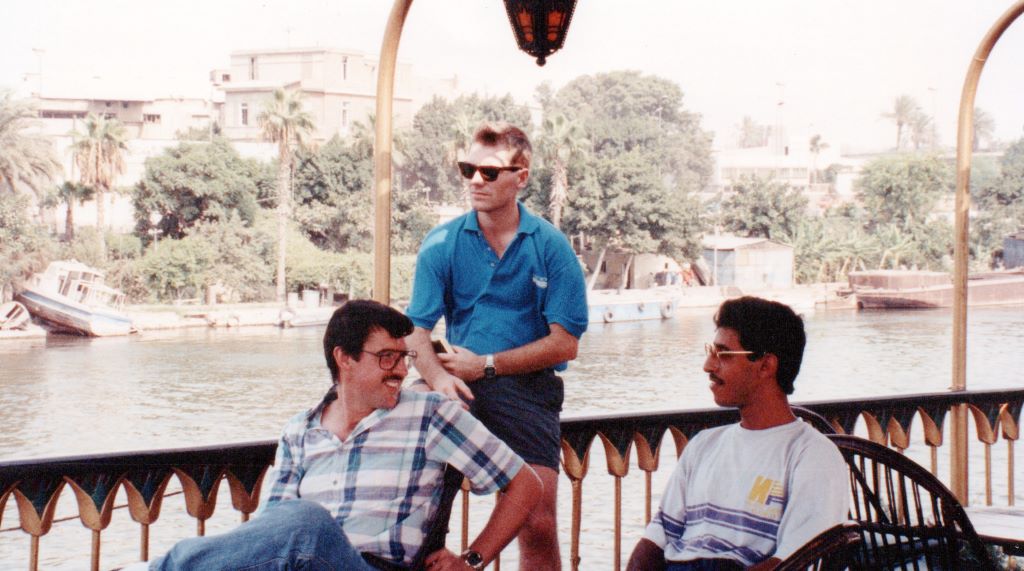

During my time in Oman, I attended additional training classes in Dubai and Cairo, and such excursions were a real treat to get out of the desert. I also passed through Qatar and Bahrain. While the job was challenging and adventurous and the pay was good, the work schedule was particularly attractive, enabling a 3-week trip every three months, and a big two-month trip at the end of each year. While I used some of this time to catch up with family and friends, my various trips also took me skiing in France, on safari in Kenya, holidaying in Thailand, visiting friends in Russia, and sailing in Spain. For my first big trip, I joined an expedition to Irian Jaya in Indonesia which resulted in Dr Roy Wiles naming a watermite after me as I helped discover it (corticacarus irelandi). For the second big trip, I toured Australia seeing friends in Melbourne and Hobart and diving the Great Barrier Reef.

While all of this traveling was a lot of fun, it became lonely. Continuously meeting new interesting people was fascinating, and I was able to do some trips with friends from college. I yearned stability, but fortunately it was a minority of the time. During those travels, I only once considered another job. During my visit to Russia, we were in Red Square during the first May Day demonstrations after the fall of communism, and I photographed the demonstration. I loved being close to such action and emotion while being detached and recording it. I did see one camera crew get beaten up which was a bit concerning.

Here are some pictures from my various non-work adventures while I was based in Marmul:

Once I had “broken out” and was no longer a trainee, the training had not stopped. Structured learning continued with the to achieve “General Field Engineer” (GFE) before three years seniority. Even though we were busy in the desert, we had little to do in our down time which facilitated progress. Achieving GFE required two final hurdles: completing a significant project and passing a series of verbal exams called “GFE Control” at the area headquarters in Dubai. My project was field testing some new equipment called the Azimuthal Laterolog (ALAT) and writing the operations manual for it. I found a design issue which I fed back to the project manager in Paris, Dylan Davies. Dylan accepted the design change, and twelve years later, transferred me to work with him in Southampton.

Before my final “GFE control,” I had a local review in Muscat with our division management. The toughest part of this was a one-hour conversation with John Edwards, our marketing manager from New Zealand, about neutrons. When I was struggling to explain some of the physics, I steered the conversation onto adventure and was happy to learn John was planning a trip to Venezuela. I was quick to offer him a copy of the guidebook that I had contributed to from my pre-Schlumberger trip to Venezuela and was able to pass the review. However, there was a bunch of feedback on my project presentation and my efforts caused me to miss my flight to Dubai. I was able to catch a later flight to Abu Dhabi and catch a taxi to Dubai. My taxi driver drove like a maniac, was probably drunk, and I have not been more scared in my life. However, I made it alive to Dubai and passed my GFE Control the following day. That signaled the end of my time in Oman, and I took my two-month vacation to Australia before starting my next assignment in Aberdeen, Scotland. My luggage still consisted of one duffel bag!

March 1994 to May 1995: Aberdeen, Scotland

I felt I deserved a reward for completing my GFE but I was cognizant of what my tutor John had told me about saving. I treated myself to an upgraded SLR camera and lens. The camera body was a film-based Nikon F90 and is long retired. However, the lens was the Nikkor 80-200m F2.8 lens, which I am still using thirty years later, though I am now considering an upgrade! I don’t have any work photos from my time in Aberdeen as the work was offshore and cameras were not allowed. After survival training which includes a simulated helicopter capsize, you can go offshore. The environment could not have been more different than Oman, with much extreme weather. Helicopter flights were unpredictable. One chopper that I was on turned around because the wind was so strong that they were not making sufficient headway. Another time, we just dropped several hundred feet when we hit an air pocket. Another time, I was stranded on a rig because of dense fog, even though we could hear the chopper’s rotors above the helideck. In the winter on one rig, large chunks of ice were falling around me as I checked tools. In the summer, on a rig off the north coast of Scotland, the sun barely set and it was never dark. I remember a thankfully uneventful trip to a job in Ireland. Having some photos of these would have been great. While the offshore experiences were fun, the morale in the base was particularly low. Many people had joined Schlumberger with the expectation of an international career yet they were “stuck” in Aberdeen which had long, grey, depressing winters. I made the most of my time there, having fun at and outside work, until another internal opportunity allowed me to do something new.

As a GFE and a relatively experienced engineer, I was sent on the more challenging jobs, and issues seemed to follow me. I remember an inexperienced company man causing my cable to get snapped on a complex fishing job and amazingly no one got hurt. On another fishing job, the drillers pulled so hard on my logging tools that they snapped them downhole. Probably the most memorable was when I was part of the crew responsible for setting off explosive perforations that would produce the first oil on a brand-new platform. The platform had the new computer system, which was my expertise, but only one engineer was allowed on the platform at a time, so we did a handover on the walkway to a semisubmersible rig which is where we slept. However, a winter storm blew in, which knocked one of my crew off his feet causing a dislocated shoulder, so he needed to be medevacked. The storm got worse, and we had to shut down operations and the semisub had to disconnect, and I was “stranded” on the platform with my crew. The quarters on the platform, designed for oil company employees rather than contractors, were luxurious and we felt the lack of welcome! After the storm subsided, we completed the job and all was good.

While work was adventurous, there was a lot of waiting around; either waiting for the previous operation to finish, or the frequent “waiting on weather.” I made the most of my time outside of work, joining the local Octopush (underwater hockey) club, SCUBA diving, completing triathlons, and hiking in the Scottish Highlands and the West coast. My one overseas trip was paragliding in Spain with Rob Willings who I shared a house with, and one day we nipped over the border to Gibraltar. When I first arrived in Aberdeen, work put me in a flat by myself. It was cold, dark, and very quiet, and immediately made me very depressed. After three years in the desert, I was craving a social life. I spoke to other engineers and learned about a staff house that had one of its six bedrooms available, so I moved. It was the best decision of my time in Aberdeen, and we had a blast at 406, Great Western Road. I computed to work by bike and was very lucky to walk away from a collision when I somersaulted over a car. However, I made the most of the opportunity to get a better bike for the triathlon, which I still have!

During my time in Aberdeen, I was lead engineer for one client and I stood in for the Field Service Manager (FSM) when he was on vacation. I sensed that my next step would be an FSM but I did not want an office job yet. I enjoyed the excitement of the field. Before the end of my first year in Aberdeen, I saw an advert posted on the wall of the break room from a sister company, Anadrill, looking for engineers to cross train. Anadrill were more involved with drilling wells, steering them directionally and taking measurements, with the measurements slowly catching up to the type of measurements taken on Wireline. I liked the idea of this, having enjoyed working closely with the drilling rig crew when running TLC jobs in Oman. I applied and was accepted. I was to start in the US in June 1995 with an initial month in Lafayette and then a training school in Houston.

But first, I had to use up some accrued vacation days or I would lose them. I joined a SCUBA diving project in Belize that was surveying the reef. I also visited Vicky Weth from college who was living and working on Bermuda where I SCUBA dived and walked from one end of Bermuda to the other. Unfortunately, I don’t have photos of either of those, but I did get lots from a trip I took to Ecuador in May 1995 with James Mead and James Pearce-Smith from college. I can remember very little of the Ecuador trip, even when I returned to Ecuador for work in 2015, and I think the altitude might have affected my memory.

June 1995: Lafayette

For this transfer, in addition to my suitcase, I shipped one item – the bike that I had bought in Aberdeen. However, by the time I made it to the USA and joined Anadrill, the transfer of the other engineers had stopped so there was not a cross-training program for me to join. Jim Aivalis, the manager in Lafayette, worked out the basics and let me work out the rest. I was to spend an introductory month in Lafayette and get some basic exposure to Anadrill and then attend training schools in Houston, finding the ones that would best develop me. This was my first time in the USA and the first person I met was a true Texan called Irless Brooks who had the strongest Texas drawl I could imagine and was so welcoming. Also, I had expected the US to be quite similar to the UK, but the difference caused me to suffer the greatest culture shock I ever experienced. My first night as I was passing through Houston, I chose to eat at a restaurant (IHOP) that was very close to my hotel, so I walked to it, without realizing the challenge of walking across ten lanes of traffic. I was also stressed out by the way you paid the bill, and what about tipping?

In Lafayette, I initially stayed at the Red Roof Inn (which was quite grim) and it was suggested that I could stay in a staff apartment that was used by engineers who lived out of town. One such engineer was Eric Tyburec who lived in Austin. The staff house was perfect for when I was not offshore. I was also allowed to use a company car which I took with me to Houston for my training schools. Eric was a keen cyclist, and we went on many rides together around Lafayette. He was not a triathlete and I managed to complete one race in Lafayette. I remember one particular ride when a thunderstorm came through and I was sure I had been hit by lightning in the torrential rain.

My main memory is two things from my first trip offshore with Eric, who was known for his bluntness. At one point, he offered me a piece of gum, which I did not take, so he suggested I do something else for my bad breath! I’ve remembered that one. Going offshore in the Gulf was quite different from the North Sea as we would normally go by boat, something that never happened in the North Sea. I had heard the stories about tricks played on people on their first trip offshore. As an experienced engineer, everyone assumed I knew what I was doing, and I did not want to admit that I had never ridden in the personnel basket, which dangles at the end of a rig crane. My fear of heights did not help the idea of hanging on the outside of that basket… Anyway, I had a few hairy transfers like that but fortunately without incident. The main incident was when a boat took on water when returning to shore after a job, so we had to put into a different port before we sunk and find our way back to our cars at the port we departed from.

The personnel manager who facilitated my transfer into Anadrill was Dennis Welborn, whom I later worked with. Dennis later informed me that I was never supposed to continue to work on the rigs for very long after transfer. They had a shortage of managers, but I managed to avoid a desk job for a while and stayed on the rigs.

July to October 1995: Houston

I headed to Houston and joined a Delta 1 training class for new hires into Anadrill, followed by classes that covered other equipment. Two instructors, Russ Neuschaefer and Steve Segal, were about my age and seniority so the classes were pretty chill though I still learned lots. I lived in the Oakwood Apartments on Voss, now the Park at Voss and about 1.5 miles from where we currently live. I made the most of the time to do local things which included watching Astros baseball, going to an Aggies football game, taking an airboat ride to see alligators, and visiting New Orleans and Austin. I also visited a friend from school, Sian Morgan, in San Francisco and climbed the Half Dome in Yosemite.

October 1995 to October 1996: Lafayette

On my return to Lafayette, I quickly “broke out” again so I could run my own jobs. However, Anadrill jobs typically had 2-3 engineers on each job as 24-hour monitoring was required for multiple weeks, and additional tasks were sometimes included. I was happy to take on the longer jobs and work the holidays, as others had family and I wanted to go on trips. I managed to get a couple in before they assigned me as a “District Engineer” to help with the move of the base from Diesel Drive in Scott, North of Lafayette, to Youngsville, South of Lafayette. This job also allowed me to prepare for an extended three-month assignment on a drillship for the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) that would come next.

I traveled to New York and San Francisco as part of the preparation for the ODP project. I also traveled to Mexico to sort out a visa and managed to turn it into a stay at Club Med, though it nearly ended in disaster when my rental car ran out of fuel. At work, I remember the particular generosity of another engineer, Nels Berggren, who invited me to join his family for Christmas lunch. Tom Rebler was one of my managers and our paths crossed several times over the next few years, including our borrowing his pop-up camper to see if we liked it. I also worked with many other fine people.

I continued to seek adventure outside of work. Through Earthwatch, I joined some scientists from the University of Idaho in Pocatello that studied mountain lions. My payment contributed to their research into Mountain Lions which was led by Dr. John Laundré and graduate student Kelly Altendorf, and I got to join them in the field for a week. A typical day was driving into the mountains with hunting dogs and a radio beacon tracker (the cats were tagged). When we picked up a radio signal, we would release the dogs and chase them on foot in deep snow. By instinct, these huge cats would climb a tree to get away from the smaller dogs, though we did not know how long it would take them to do that, which impacted the length of our walk through deep snow. On arrival at the tree, John would shoot the cat with a tranquilizer dart, which “encouraged” the animal to leap out of the tree and run again, but only for about a minute. We would measure the animal’s size, take blood samples, and refresh the radio beacon’s batteries, before it woke up, staggered around a bit, then ran away. It was so much fun. Back at work, I was at first confused by the reaction of colleagues to the photo of the cat on my shoulders. With many of them hunters, they thought I had killed the cat and were dismayed because it is an endangered species. I explained the context and I started to learn how the US hunting culture is very much about protection which was an odd paradox to a Brit.

Four months later, I visited Kelly who was doing some related work in Yellowstone and is where I met Martin Margulies who was studying bears. We had so much fun, and it was wise for me to have wildlife biologists telling me that I was close enough when trying to photograph the animals! It was the first time I’d made the most of my “big camera.” However, this crowd was unforgiving when I misidentified a marmot as a beaver, so such animals became known as beaver-like-objects.

I also spent one night backcountry camping in the Grand Teton National Park. I got a permit to camp at a designated site near Hermitage Point and I started hiking in late afternoon without any food because of bears. As sunset was approaching, I headed to the lake as I wanted to catch the view, but I did not want to leave. In darkness, I then tried to find the campsite. It was difficult to see and some coyote howling made me a little uneasy and I was worried I’d bump into a bear. I nearly did bump into a large deer, though I’m not sure who was more scared by the encounter. I never did find that campsite!

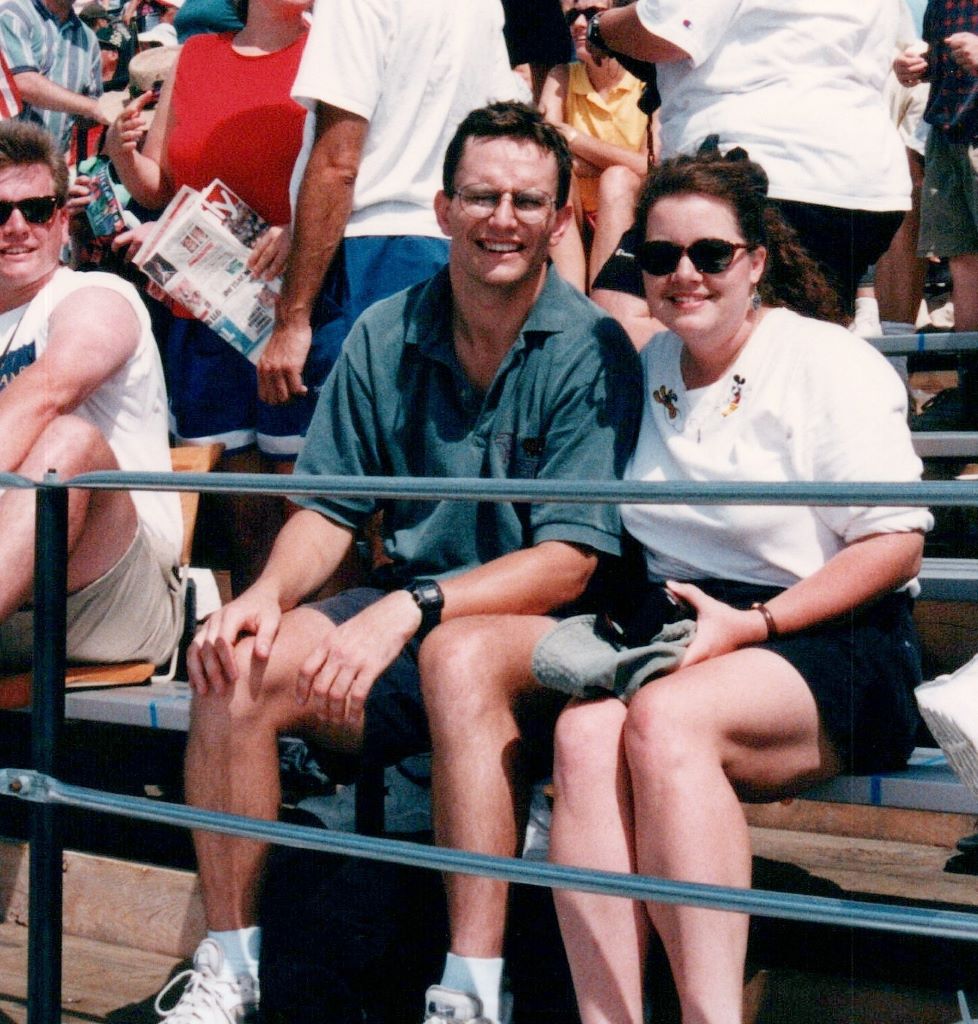

Back in Lafayette, I moved into my own apartment (Diamond Lakes then Oakwood Bend) and tried hard to develop social connections outside of work, which was still difficult. Having a near-regular job where I was not frequently heading offshore allowed me to develop a social life. I was able to attend church almost regularly and I met Janet in 1996. Janet loved to travel but her teaching job had not presented many opportunities, though she had enjoyed the family road trips around USA when growing up. I was confused at first as I mistook Janet’s identical twin sister for her! Soon after we started dating, Janet headed off to Atlanta for a catering job at the Olympics, so I argue that she ran away from me first, though I followed as I did not want to pass up a visit to the Olympics!

I knew that I would be getting on a drillship for three months in the fall so we made the most of the summer, including a visit to my school friend Emme on Grand Cayman. I tried harder to get good photos of us and have always enjoyed selfies like these.

October 1996 to January 1997: JOIDES Resolution

In October, I boarded the JOIDES Resolution, a drillship facilitating national science organizations to research the deep oceans and the earth’s crust. I was on board for ODP Legs 170 and 171a when we drilled through tectonic plate boundaries off Costa Rica and Barbados. The Costa Rica leg also included volcanologists comparing the material going into the subduction zone, under Costa Rica, with what came out of its volcanoes. Normally, the ship would core holes and then try to lower Wireline logging tools into them, but the drilled formation was so unstable that it was often unviable. This trip was the first complete leg where Logging While Drilling was going to be used, and I was on board as the sole expert. The work was very satisfying as I worked as a peer with leaders in the fields from drilling to researching methane hydrates. There was a lot of downtime as we had to sail from San Diego to the initial sites off Costa Rica, and then through the Panama Canal and across the Caribbean to get to Barbados. Christmas on board was a lot of fun with the Filippino rig crew. For my measurements, measuring the depth of my sensors on a ship free-floating in the ocean was a particular challenge, though the idle time with a bunch of experts allowed me to use Matlab to remove the relatively high-frequency effect of the ocean waves, leaving behind the forward motion of the drill bit.

The photos below show us leaving San Diego, sailing on the high seas, transiting the Panama Canal, and the dock in Barbados. While moving between locations, we could set our own work hours. I chose to work at night because of the peace. Watching each sunrise was a special time.

The scientists were very excited when the drill crew brought cores to surface as studying them was their whole reason for being on the ship.

I liked wearing my “suit,” a well-worn pair of comfortable coveralls.

The Filippino crew were such fun to “work” with, whether it was catching huge mahi mahi and barbecuing them on the rig floor or singing Christmas carols.

The downtime gave me time to take photos of the birds that hung out on the ship. The Egret on the deck was not an issue, but I had to get over my fear of heights to climb to the top of the mast, when the ship was under way, to catch the Peregrine Falcon that hung out for a while.

–

Communication off the ship was challenging, with the only photo being an Inmarsat costing $10 a minute. It was the days of email, and the ship supported it as it was important for the scientists, synchronizing twice a day. Janet and I soon worked this out and we each became extremely proficient at typing as we emailed each other every day, if not twice a day.

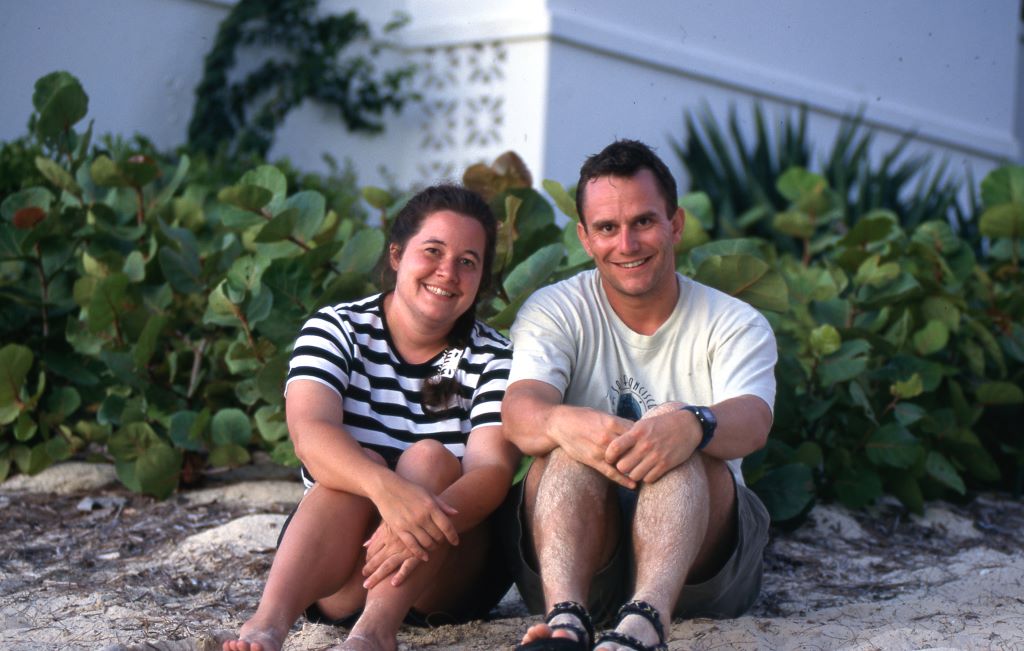

Even though the ship looks like a lot of fun, it also got old and stressful. Like living in the desert, I was eager to get off the ship after three months. We needed to get all of my equipment off the ship in Barbados, and there had previously been issues and delays getting the equipment off the island onto a plane. So, I included a few days on Barbados in my plans so I could ensure things went smoothly. We had prepared the logistics sufficiently well and the equipment got on the plane the same day, but all of my reservations were made. I wasn’t too keen to change them as Janet came to Barbados and greeted me off the boat, so we had some fun days in Barbados. On the way back in January 1997, a winter storm descended upon Texas. We managed to get into Dallas and the final leg to Lafayette kept on getting delayed. Janet had to get back to teach. Eventually, our flight was cancelled, but by then no hotel rooms were available so we spent the night on a DFW airport floor. The following morning, the flights remained cancelled, so we foolishly decided to rent a car and drive. The interstates were covered in ice and large trucks were jackknifing in front of us, but we made it to Lafayette without incident, only for Janet’s school to be cancelled! After I had organized all of my equipment that returned from the ship, I managed to squeeze in a ski trip to Club Med at Copper Mountain in Colorado (now closed) which is unmemorable, probably because I went by myself, but the altitude likely impacted my memory too. Then, it was time for my next assignment that took me to Africa. Wade Welkener, who was working in Lafayette, had worked in Pointe Noire so gave me some pointers. My parents had met and worked in Nigeria in the 50s and 60s, but much had changed.

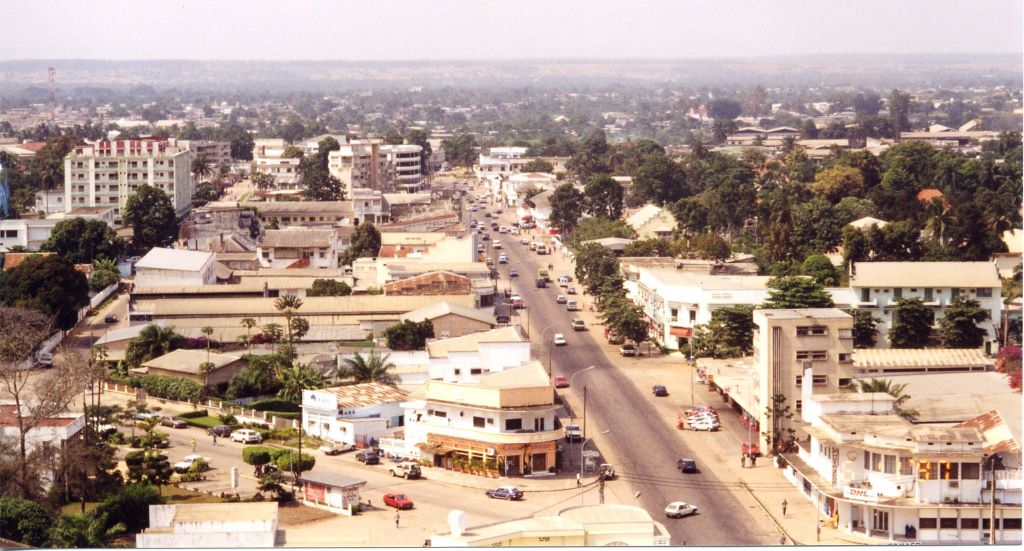

March to July 1997: Pointe Noire, Republic of Congo

My assignment was District Technical Manager for Anadrill in South West Africa. Geographically, this covered the operations in Angola, Congo, Gabon, and Cameroon. I was responsible for equipment at these locations, in particular in Congo and Angola. Angola included a self-sufficient operation dedicated to Chevron in Cabinda which was a small piece of Angolese territory separated from the rest of the country by the River Congo and a strip of land belonging to the Democratic Republic of Congo (former Zaire). I started my assignment at the Anadrill base in Pointe Noire on the Congolese coast. It had been built to serve up to four rigs off Congo. However, the ongoing civil war in Angola between MPLA (in government in Luanda) and UNITA (rebels in much of the rest of the country) led to a unique situation. The oilfield base in mainland Angola had been in Soyo on the banks of the River Congo until rebels overran it in 1992. This led to the oil company (mostly Texaco) moving their offices onto offshore rigs that were outside of shelling range from the shore. Equipment for the Angolese rigs was maintained at the Pointe Noire base, and that was the status when I arrived.

The equipment situation in Pointe Noire was dire for multiple reasons. Serving the six rigs off Angola in addition to the four Congolese meant the base was stretched to the limit. This was compounded by customs delays for equipment returning from Angolese rigs into Congo. The equipment was old and unreliable and getting spare parts was slow and logistically complex. We were plagued by the usual challenges of power and network outages. I remember one rainstorm that left two feet of water throughout the base for several days. We had some tremendous people on the ground, and I fondly remember Eric Hollebecque, the maintenance manager, who always gave 150% to look after the equipment and people. I did what I could to help, hunting down spares at other locations and persuading headquarters to allocate us some new equipment, but it would still take several months before it arrived. Morale was a tremendous challenge in a tough environment, but the team remained remarkably focused.

I initially stayed with other expat staff in the bachelor staff house, though our sales manager, Philippe Rigo, very generously offered for me to stay in his house which had a spare bedroom. His house, like most others, had its own armed guards which prevented theft and trouble, primarily through the connection it brought into the local community. He even let me stay after I flooded his house! One evening when I was getting ready for bed, I turned a water tap on and nothing came out, which was not uncommon. So, I went to bed. In the morning, I woke to the sound of sweeping, which wasn’t odd. As I listened more, it sounded strange, like someone was sweeping water, which did not make sense. I touched the floor while lying in bed and found two inches of water. Water had been restored in the night, and I had not turned off the tap I had tried the night before. In the big scheme of things that went wrong in Africa, this was minor, but I was devastated, and Philippe continued to be so gracious.

Before I left Louisiana, Janet and I had already started planning our wedding (i.e., booking a photographer), even though we were not engaged yet. As I traveled through London on my way to Africa, I passed a jeweler and realized I needed a ring and to propose! With little hesitation, I went into that shop and bought the ring that remains on her finger. It was difficult being apart from each other. Phone lines remained poor and expensive, so our dating continued by email, including organizing the details of Janet’s visit in early June.

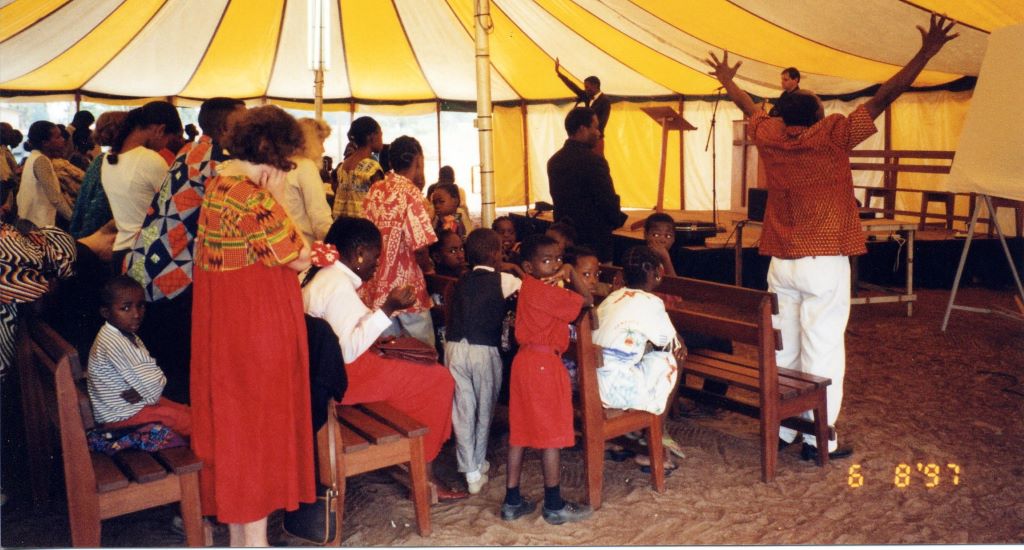

With a marriage on the horizon, I decided I needed to take my Christian faith more seriously. Eric Hollebecque had mentioned a church run by an expat couple in a circus tent by the airport and I became a regular attendee of a congregation led by Gary and Janice Dickinson, US missionaries with the Assembly of God. The messages and singing were in French (mine was weak) with some translation into the local language, Munukutubu. The congregation was a fascinating mixture of locals, expats, and Russian women. The Russian women had married Congolese men who had visited Moscow for education, looking for an escape from Russia. That church was where I have most clearly felt the presence of the Holy Spirit, while in contrast, I felt the presence of evil most strongly when driving around town. For Gary and Janice, Pointe Noire was home. They sent their teenage daughters to boarding school in East Africa before they attended college in the US. Gary had been ravaged by disease but was miraculously healed on multiple occasions. They have continued planting churches in this region, and after twenty-four years in Congo, moved to Libreville in Gabon, just up the coast, to establish a Bible school. I saw how they were largely on-their-own while I was supported by Schlumberger. I realized that their work required a strong calling, one that I did not have! On 4 May, Gary baptized me in Pointe Noire harbor.

Part of the preparation for Janet’s visit was a slew of inoculations and she hated needles, so I joke that this was the test she needed to pass before I would marry her! Janet arrived in Pointe Noire on 3 June 1997, having been travelling for more than 24 hours from Lafayette, via Houston, Switzerland, Johannesburg, and Brazzaville. It was fantastic to see her, and I phoned her Mom to let her know that she had arrived as I was sure she would be worrying. However, as I still continue to experience in the US, my accent causes people to think my pronunciation of “Peter” is “pizza.” So, on a poor phone line, it took me some time to convince her that I was not trying to sell her pizza, but that I had her daughter, albeit safe and sound!

We had about two weeks in Pointe Noire before a planned trip to London for some training and a trip to Ireland. However, a shadow immediately fell when there was a coup on 5 June, and the lady who had helped Janet through customs in Brazzaville was raped and killed. It remained stable in Pointe Noire while we were there and we managed to see the sites and have some fun. I was able to quietly propose to Janet in Philippe’s house, presented the ring, and then warned her that it was too dangerous to wear it outside. Did she really want to be with this guy? On 15th June, we were scheduled to leave for a training course, but this coincided with when many companies had told their non-essential expat personnel to leave because the aftermath of the coup was approaching Pointe Noire. Our Air Afrique plane did a tour of West Africa on its way to Paris. I had a bout of terrible food poisoning so remember little about that flight except a stop in Ouagadougou in Burkina Fasa. I also remember that, to help us board earlier so I could sit down, we “helped” another Schlumberger mother with her children get on the plane. I also learned that if you sit on the plane looking green and holding a sick bag, no one will choose to sit next to you!

After the trip when I returned to Luanda, I frequently spoke with Eric who remained in Pointe Noire. There was martial law and the military stacked dead bodies at the end of his road. The beef was not with expats but they took his vehicle. It settled down and I returned later to visit. I remain amazed at how Eric took all of this in his stride.

During my time in Pointe Noire, spending time with the Dickinson and Mary families helped with my sanity.

There was a beach bar/restaurant right here that we frequented. On one of my journeys here, I sped past a police car as I was in a hurry to get to the beach! They followed me and asked me to stop, but I was wary, so I followed them to the Police Station where I paid my fine and signed their book. This is also the restaurant we ate at before our “evacuation” flight, and I think it was the shrimp that did not agree with me. When we were waiting to board the flight at the airport, we were herded like cattle into an airless room. I made the most of the fresh air by the exit gate, but a pushy well-dressed woman insisted she was at the front of the line and forced her way next to me. I had little pity when my vomit, that I tried to project through the bars of the gate, back splashed onto her very expensive shoes.

After attending the training course in London, we spent some time in England with my parents and Janet’s friend Jennifer who came to visit, and then Janet and I headed off to Ireland for ten days. Having heard so much about the prevalence of rain, and hence the country’s greenness, we realized the blessing of having beautiful weather throughout our visit with just one short rain shower. We had a lot of fun doing so many different things from kissing the Blarney stone, horse riding, pitch and putt (I am not allowed to forget that I lost!), the Cliffs of Moher (I was terrified), and the Dingle Peninsula.

July 1997 to January 1998: Luanda and Soyo, Angola

After the trip to Ireland, it was better to return to Luanda rather than Pointe Noire because of the instability. Also, the renovation of the Soyo base had progressed sufficiently for operations to restart from it. While operating out of Soyo helped by avoiding Congo customs, there were the expected challenges associated with starting a new base. There were multiple Schlumberger product lines at the Soyo base, all trying to restart their operations, and the sense of comradery was fantastic. Life in Soyo was straightforward as one only had to worry about work; we lived in a camp with catered food, though my first trip to Soyo had been somewhat unnerving. As the plane approached the runway, you spotted a couple of plane wreckages and some surface-to-air missiles. Having landed, the main door of the ten-seat aircraft was stuck, and it took them fifteen minutes to open. When we drove off base, there were white or red painted stakes in the ground on either side of the road. White meant the land had been cleared of landmines, but the clearers were South African mercenaries in whom I did not have total confidence. If I needed to turn around in the road, I was especially careful not to drive off road into an adjacent field, even when the stakes were white. I remember seeing a group of children running through such a field. Nothing happened, but I still get chills thinking about it.

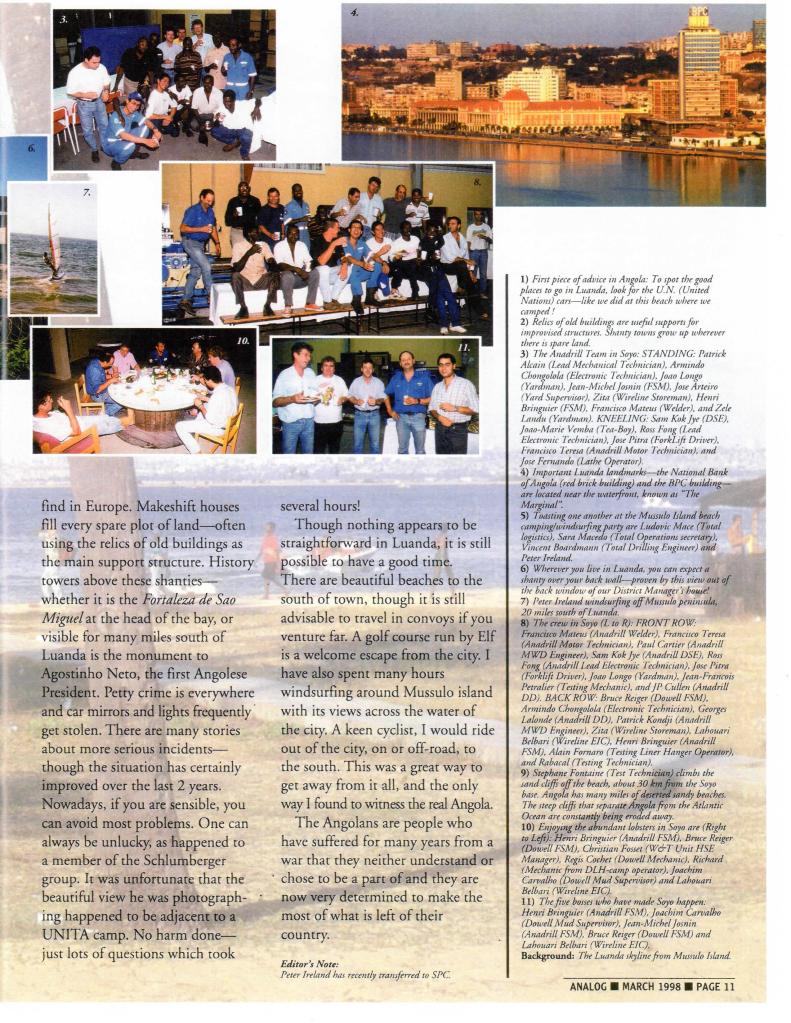

The article below, which I wrote for the internal company magazine shortly after I transferred out of Angola, captures what it was like “rebuilding Soyo.” All photos are my own. I had a good zoom lens to photograph the surface-to-air missile from the road, as I was concerned there were landmines in the field. Paul Cartier, who I worked with in Houston two decades later, found what appeared to be live ammunition on the tank.

I was based in the Luanda office with my boss the district manager, Christian Fassinou from the Ivory Coast. There were only the two of us in the Anadrill office, and I had to cover for Christian when he was out of town. We had very demanding clients who would call for us on a radio and we would need to shuffle personnel and equipment, or just go and take a beating. We had as good support as possible from London and Houston, but we worked long hours, plagued by the power and network outages. When someone started renovating the office next door, they got loud, but when they actually punched a hole in the wall, I just gave up and went to the beach! We started building a new base with offices in the port while I was there. I would often leave the office after dark, being careful not to bump into someone who was standing in the street with a machine gun. Any time an engineer came through town on their way to or from an offshore rig, it was an excuse to take them to eat and show them town.

The streets were full of kids looking for something. As you drove around, you saw them breaking into cars. If you gave them something when you parked, like a T-shirt, your car was safer. I was not good at understanding this hustle and my car was broken into a couple of times and stolen shortly before I left. There were few landmine victims in Luanda as the government had removed the limbless from Luanda as it deterred foreign investment. I had a couple of minor run-ins with the police, which was difficult as I spoke very little Portuguese. One time, a policeman flagged me down, got in my car, and told me where to drive. I was on the radio trying to get someone from work to speak to him, but it was lunch time and no one answered. With much relief, I ended up dropping him at the Police station on the outskirts of town – he had just wanted a lift!

I stayed in an apartment which was basic with a guard. I welcomed Christian’s invitation to stay in his house when he was away as it had a cook and had much more space. One challenge in my apartment was the intermittency of both the water and electricity. I kept a 40-gallon bin full of water so that I could flush the toilet. However, as I travelled, I did not know how long the electricity was off for, and hence the impact on items in the freezer, which I did not think about. I remember a horrific bout of food poisoning after eating a frozen savoury pancake that had thawed and refrozen. Lying in bed, it was like there was a hand pressing on my chest holding me in bed. The water heater was gas and sometimes would not light and I burnt my eyebrows when lighting it. I won’t talk about the cockroaches…

While I could buy flatbread from a 40-ft container just outside my apartment, the main grocery store that I used was one run by an oil company but it was only open 9am-5pm during the week, so I had to make a point of blocking off part of my work day. With my itinerary uncertain and lots of opportunities to take visiting engineers out to eat, and after my frozen pancake incident, I did not cook much at home and my waistline suffered. Groceries and restaurants were both very expensive but there was little choice.

Janet stayed in Luanda for a couple of weeks after our trip to England and Ireland. This was largely because it was safer in Angola, where the active civil war was not encroaching on Luanda, than in Pointe Noire with its recent coup. However, Luanda felt much less safe for her than Pointe Noire had been, and I did not know anyone outside of work. She was stuck in the apartment all day. The only English-language station was an international CNN station which played the same news report every thirty minutes. A highlight of the day was making chocolate chip cookies for the guard, having broken up a chocolate bar as chocolate chips were not for sale. When I was not working, we explored what we could. This included a slave museum just outside Luanda. Louisiana’s state penitentiary is known as “Angola” because the land it is situated on used to be a plantation with many enslaved persons who had come from Angola.

For a short period of time, it was a fascinating adventure.

I remember two interesting culinary experiences. One time, I was stuck at Cabinda airport but was happy to see they had a restaurant. The menu was in Portuguese, and no one spoke English. I looked at the menu and though a word looked like “Pizza” which seemed safe. However, “peixe” means fish, though the resulting seafood dish was one of the best I have ever tasted! The second culinary memory is from a seafood restaurant that I visited with Janet. We visited a recommended restaurant, though were unsure what to order. We ended up ordering enough food for eight people, but we didn’t like any of it!

Shortly after I arrived in Africa, I received an email from Vincent Bordmann who had been a friend during my initial Schlumberger training school ETC-35 six years earlier. After three years with Schlumberger in Yemen, Vincent had joined Total. He was transferring to Luanda and wanted to know whether I wanted to include a windsurfer and mountain bike in his container. I happily accepted the offer and welcomed Vincent’s arrival for multiple reasons. First, he became my main client, and while not giving me special treatment, was more reasonable than the other clients. He was particularly interested in using the new technology that I had been able to bring into the country and was very apologetic when he got it stuck and had to abandon it! However, it was having a fellow explorer that particularly helped my sanity. Total had a large camp and he had other friends who he worked with. We could go windsurfing out of town and eat at a fine seafood restaurant. We would go offroad cycling without the fear of landmines as it was on the edge of ploughed fields. We would intentionally carry no ID or money and claim to speak no Portuguese (which was accurate!) so that when a military checkpoint stopped us, they didn’t know what to do with us! We understood that they did not have bullets in their guns to prevent them rebelling against the leaders. I fondly remember these times with Vincent when we escaped for a few hours before returning to the reality of work and life.

I escaped in November 1997 for a trip with Janet to visit her family in Maine. We were getting married in February the next year and had decided we were not going to live in Angola. I had let my managers know and they came through with a transfer to Sugar Land in Texas. However, I accept that Angola partially “broke” me. While the challenging work or the difficult lifestyle would have been enough by themselves, together they were too much. There were times when, if I could have gone to the airport and bought a plane ticket (it did not work that way), I would have just left. I found a way to cope, and I compare it to a pressure relief valve. The pressure would build to a certain point, and then it just would not build any more. I learnt to prioritize what mattered most and get through each day, though it was not a lifestyle I wanted when married.

Phase 1: March 1991 to January 1998. A Reflection on Operations

The first seven years are “phase 1” of my career when I was young, free, and single. In my twenties, the excitement of adventure drove me, coupled with the hunger for responsibility at work. It was an amazing ride, but it got old. The work challenge got less attractive as it was always firefighting, figurative fires that needed to be put out rapidly as there was likely to be an even bigger crisis the following day. Even longer-term changes, like establishing the base in Soyo, were soon superseded by changes in the business or political landscape. The adventurous lifestyle was a lot of fun, but it got lonely. Some people appear to thrive on this for many years. Others get married and have children while continuing to work in these types of environments, but I had reached a turning point. My researching the above for this blog has brought back many memories, but mostly, it reminded me of so many great people that I worked with, and I went digging to see where they are now, and I found a whole spectrum. Most had left Schlumberger at some point and worked for other companies or set up their own. A few had retired after even more years with Schlumberger than my thirty. I found obituaries and recognized so many names in comments. While I met many more people in the subsequent years of my career, those I met in these first seven years shared the adventure of “the field” so there is a greater connection.

February 1998: In Transition

I was very happy to get on the plane to leave Angola for my wedding and honeymoon. As I passed through England a week before the wedding, I had arranged a stag weekend with five friends from college. We had booked a cottage in the hills and were going to eat a huge roast dinner and do some hiking. The day before the others arrived, James and I checked in early and did some exploring. I started to feel weak and shivery. That night, I had a raging fever in bed and can remember little though I am sure the guys had a great time! Schlumberger did not have the anti-malarial programs that they have since developed. In Africa, the anti-malarial pills had affected my mood, which was the last thing I needed, so I had stopped taking them. However, on arrival in Pointe Noire, Eric had told me about a medicine Mepacrine to always have with me, and to start taking if I developed a fever! I later discovered it had been developed by the US military when building the Panama Canal. So, I took some of it. The following morning, I awoke feeling terrible, but I had to catch a plane to get to my wedding! It was a frosty morning, and I remember using a credit card to scrape the ice off the windscreen. I had been planning to carry on a pilot’s case full of papers and negatives and slides, as they were my most important possessions, but I did not have the strength to carry it, so I checked it. At each check point at the airport, I did my best to look well as I did not want to be turned away and miss my wedding. I sensed that if I took myself off the flight, I would feel better within thirty minutes. I made it onto the plane and fortunately, had three seats to myself. For the whole flight, I alternated every ten minutes between raging sweats and shivering uncontrollably. Janet met me off the plane, though I could not find my pilot’s case on the luggage carousel! We filed the paperwork for missing luggage and had just left the airport when I received an email from someone who had my bag at their hotel. They said they had found it in the bathrooms at the airport. It all sounded very weird. We went to retrieve my bag and the only thing that appeared to have been stolen was a Leatherman. It was strange but the least of my concerns.

We had a packed agenda in Houston, and I expected my sickness to pass. We met the visa lawyers and checked the progress of a new home in Sugar Land that was being built for us. We stayed with Janet’s friend Allison, who used her pharmaceutical background to research the medicine I was taking. After sorting things out in Houston, we headed to Lafayette. I wasn’t feeling better, so I finally visited a doctor at a walk-in clinic. He took blood tests and even reached out to the CDC. However, they could not detect a disease and the Mepacrine had wreaked havoc with my Liver enzyme counts which hindered diagnosis. All that he could recommend was to treat the symptoms (seriously, take two aspirin!) and wait for the body to defeat it. It was an emotional and tiring week, and I pictured myself in the church on a gurney for our wedding. On our wedding day, I was perhaps 75% recovered.

Our honeymoon started with a relaxed few days in a mountain cabin in North Arkansas, which allowed my recovery to complete before we headed to an activity-filled adventure in Costa Rica. Janet had planned all of our honeymoon on the internet using her WebTV dial-up terminal, which was groundbreaking in 1998! After Costa Rica, we headed to England for a reception, followed by a trip to Paris to get my US visa. As the visa was going to take a couple of days, we had a fine extension to our honeymoon in Paris courtesy of Schlumberger! However, the honeymoon had to end, and we were soon heading to Sugar Land to start the next phase of my career and our lives.

March 1998 to January 2000: Sugar Land

My job was a Data Quality Engineer, working for Philippe Theys at the Sugar Land Product Center (SPC). SPC made equipment for both Wireline and Anadrill so my background in both businesses was valuable. The job was somewhat strange as much of it was internal evangelization about the importance of data quality. I helped Philippe train clients, and I taught at the training school. I also edited Anadrill’s Log Quality Manual and provided input into Philippe’s book on Log Data Acquisition and Quality Control. Steve Eddy was a fine colleague as we worked together under Philippe. Compared to my previous jobs, this was like a sabbatical. Janet joined me on a business trip to Aberdeen in June 1998 when we spent time with the Neuschaefers and Vincent as well as having a lot of fun checking out the Highlands. My next business trip was to St Johns, Newfoundland, in July 1999. Janet suggested we drive, which I at first found crazy, but I warmed to the idea, and we had a fantastic trip staying with friends and family en route, and the Newfoundlanders were so welcoming.

When I arrived in Sugar Land, the team at the Austin Technology Center had recently started working on the next acquisition system for Wireline and Anadrill (replacing MAXIS and IDEAL). They were looking for volunteers to provide input and feedback on their ideas, and Philippe was keen to get input from the data quality side. The system had a tremendous impact on the quality of its resulting products. I was also extremely interested in providing input on usability. I visited the team in Austin and was amazed by their facility but was careful about sharing any hope to work there. I had had a “Career Orientation Review” with the Sugar Land Product Center manager, who had succinctly informed me that people like me with a field background had no future in Schlumberger’s technology development. The Austin team published ideas online and invited feedback, and I provided more feedback than everyone else combined! It led to an offer to transfer to Austin in January 2000 which I happily accepted.

As I reflect on my move from the field/operations into the Product Center, the statement from the SPC manager that I had no future in technology development had some validity. The profile of the people that Schlumberger recruits for operations is very different to those recruited for technology development. Senior managers might cross over, but I was far from that. While I had a Mechanical Engineering degree, I had not practiced mechanical engineering. I knew how operations worked, and there were many people like that. I was not able to design complex mechanical or electrical circuits. Looking back, I was “lucky” to land in Austin’s software team where my career found a home for the next six years.

I smile when I remember one occasion in March 1999. Philippe knew of my interest in photography and recruited me to take photos of a retirement party for a large group of employees. Business conditions were such that the company was encouraging early retirement and I wondered whether that might happen to me.

The lower-intensity job in Sugar Land allowed the newly married couple to do a lot of exploring Texas State Parks. As well as the trip to Aberdeen and the epic road trip to Newfoundland, we headed out west to Big Bend. We had established our first home in New Territory, a housing development close to the Schlumberger facility, but it was time to move again after less than two years. Janet had had to quit her teaching job when we got married and she found it difficult to leave a class mid-year for the second time in two years. Previous moves had involved little more than a couple of suitcases. The company helped arrange movers who packed everything. We also had two cars and a pair of cats, but the three-hour drive to Austin was straightforward. We had found a house and timed the sale of our Sugar Land house with the purchase of our Austin one. This was a completely different type of move from my previous ones, aligned with my now being married and no longer in the field.

January 2000 to July 2005: Austin

When you arrived at the Austin Technology Center (ATC), even the car park suggested it was different from other Schlumberger sites with unmarked parking spots amongst the cedar trees. Nestled in Texas’s Hill Country, the main buildings were like indoor arboretums with high glass ceilings, filled with various trees and shrubs. The closest restaurant was “The Oasis,” overlooking Lake Travis and famous for sunsets, though ATC had its own excellent cafeteria and held frequent deck parties, featuring employee bands with creative names such as the Blue Screen of Death. This was the time of the dot com bubble, which Austin was a part of, and ATC wished to attract the best software talent. On entering the buildings, one was struck by the peace and quiet. The halls around the arboretum were mostly empty with perhaps a couple of people talking over coffee. This seemed like it would be an amazing place to work.

While it was an amazing place to work, the above were not the main factors. While it appeared as the most chill place I worked, it was where I put in the most hours and worked the hardest of my career with arguably the most diverse and talented group of people. About a hundred of us were working on the largest project within Schlumberger, called Horizon. The technical challenge was enormous while the usability goal was very high, and like many software projects, initial estimates of time and cost were too low which increased the pressure. The external pressure complemented the pressure everyone put on themselves to complete the functionality with the highest quality by the required deadline. The quiet corridors were disrupted by two notable events. First, if the network went down, it was like stirring up an ant nest, and people would appear from everywhere. Second, when a deadline was approaching (which seemed like every month), many would work late and would appear from their dark offices when dinner was announced, often a scrumptious Indian meal from a local restaurant.

I had three different roles during our five years in Austin and they focused on the User’s (i.e. the Field Engineer) interest. I started off as the Horizon Drilling Group Leader for 1.5 years, evolving Horizon’s vision for drilling users and releasing a prototype called DD Direct. As the project grew, I became the Horizon Products Project Manager for three years, overseeing a team of 50 engineers in four different centers around the world (ATC in Austin, SPC in Sugar Land, BGC in Beijing, and Bangalore), implementing the user workflows. For our final year in Austin, I was the Horizon Quality and Testing Manager.

The comradery within the teams was strong, with the workload and importance of deadlines building teamwork like in the field. However, we all went home every night (well, most nights) to our families, and the comradery extended to them, especially when babies came, of which there were plenty. Dearest Carol Prochnow was the force that bound us together and kept us sane. I worked with so many great people in Austin that I could write pages just about them, but I won’t. Carol stood out amongst them all. My other managers during this time were Rajat Sood and Paul Till. When I was managing the Horizon Products team, Padmanaban Namasivayam (known as Padu) was indispensable as the software development expert in my team. Julian Anigbogu and Tracy Myers were my peer-managers. The two that I worked most closely with were Adrian Francis and Greg Wibben, and between us we wrote the detailed user specifications of the system and explained them to the software developers. I fear that I offend many others by not mentioning them by name. The photos below bring back many memories.

I remember when Tony Ellis joined the team as another key Anadrill advocate. We also both played Octopush (underwater hockey)! He stayed with us when he first arrived. The visible culture shock that Tony experienced reminded me of when I first came to the US. For a Brit like me or an Australian like Tony, we expected the US to be familiar, in contrast to other countries that we knew were different but learnt otherwise.

It is difficult to describe more about what we did. We were building an extremely large and complex software system, with a release of a subset unviable. For various reasons, Schlumberger closed ATC and moved the Horizon project to China before its first release. The internal milestones that we achieved in Austin through sweating blood blur into insignificance, but the memories of people remain vivid. We were creating new workflow concepts, and when the Intellectual Property lawyers asked for patent applications, it was easy to submit many and I received several patent awards with my coworkers. Managing global teams also gave me the opportunity to travel to other Schlumberger sites around the globe which I always found fascinating, insightful, and rewarding.

Due to working across multiple time zones, we started work early and continued late, either at the office or at home.

.

This photo reminds me of the tremendous cultural diversity that we had in the team. I remember counting fourteen nationalities. I once was asked about ethnicities for some required US reporting, and I realized how unaware I was of the diversity. Cultural differences were interesting and celebrated. While there was significant diversity for most of my assignments in Schlumberger, none were as positively intertwined as during our time in Austin.

My path and Paul Thomas’s (center of second row) would touch several times in the future. He was at Sensa in Southampton and was the Completions Quality Manager some years after me. He recommended climbing “Fools Peak” when I was looking for some good scrambling with Samuel, and we had a fantastic time on it in 2018.

Work trips included Stonehouse, the British Training Center, Paris, and Grenoble in May 2002, and an around-the-world trip to Bangalore, Beijing, and Tokyo in September 2003. I also completed a Master’s in Engineering Management at the University of Texas in Austin between September 2001 and August 2003, with the final six months being particularly challenging as Bailey was born in March.

Our lifestyle completely changed in Austin as both our children were born there. We started off our time there with a house refurbishment and a lot of involvement in a church. Janet did not wish to leave a class mid-year again, so she worked as a bank teller until Bailey was born. We enjoyed travelling around Europe by train in March 2001, visiting the Outer Hebrides after a friend’s wedding in Clumber Park in England, with other trips to Edinburgh and Versailles. I joined a ministry trip to Nicaragua to drill a water well for an orphanage in July 2004. I even did a couple of bridal photo shoots at the Texas State Capitol. To help us explore, we started Geocaching in June 2002 and have continued to enjoy it. Bailey arrived in March 2003 and Samuel in September 2004, but we tried not to slow down our travelling and Bailey enjoyed fine trips to Paris, Grenoble, Mexico and Belize. Soon after Samuel was born, we learned the project was moving to Beijing and we would be moving with it so we had an extended six months of being “in limbo,” knowing that we would be moving soon. We managed to squeeze in a final “hurrah” visit to Jamaica in between a house hunting trip to Beijing, packing, and selling the house.

July 2005 to July 2006: Beijing

(Some blogs that I wrote during our time in China are here)

My role as Quality and Testing Manager for the Beijing Geoscience Center (BGC) had two primary goals. The first was to assist in the successful transition of the Horizon project from Austin to Beijing, with the project rebranded as Maxwell. The second was to establish a Software Quality and Testing organization at BGC. Many of the great people that I had worked with in Austin moved to Beijing. People moved for either a one year or three-year assignment, but that tended to change. For instance, I was supposed to be there for three years but moved on after one. There were also several great people who I worked with in Beijing, in particular Di Cao and Xu ZhiYu (known as Da Yu). The cultural difference with the locals was a barrier, and the strong bonds within the crowd from Austin probably caused us to be a bit of a clique. I became less involved in the project’s direction which was quite demotivating but was an essential part of the transition. Beijing was not my most joyful assignment, but I had fun establishing the Quality and Testing organization and there was mild satisfaction that I helped steer the project into its first Alpha field test, having worked on it for nearly seven years.

As the priority was to develop local talent, we could give the locally-hired software engineers responsibility, early. The center had recruited well from local universities so there were plenty of opportunities, but the difference in backgrounds meant I had several things to learn. I soon learned that if I was in the room, the team would speak English and look to me for direction or affirmation. They worked much faster, took more ownership, and were more creative when I left! The different approach to teamwork and creativity is probably due to different education systems. Even the nature of the Chinese language being characters rather than letters develops the brain in different ways. Though we studied Chinese, my ability struggled to improve beyond what I needed to chat to a Taxi driver! The relative salaries and living conditions for expats compared to locals were vastly different. Conversations about recent history were challenging as we knew so little of the West’s involvement in China. One engineer had grown up in one of the most polluted areas of Beijing, and when I asked him what it was like, his response was that the pollution was irrelevant as they were lucky to have food on the table. And he had gone on to graduate with a master’s degree from one of the best universities in the country. When we went out for team lunches, we had to explain that we liked to eat chicken, pork, or beef, and if it was chicken, we preferred to have neither the head nor the feet on the plate. I could tell the local engineers struggled to understand our pickiness about food. Hence, I particularly appreciated working with Da Yu, who had worked in the US and understood more about the Western perspective. We worked hard setting up the testing lab in our building, though we had most fun trying to find a well we could use for testing our software (like the Blanco test well in Austin).

I have fond memories of my cycle commute as it was a celebration of all the senses and allowed me to get as close as feasible to the “real” Beijing life. I wrote this blog at the time.

We also visited the Schlumberger facilities in Tanggu and Shekou. It is fascinating how maybe 75% of the Schlumberger culture persists in any Schlumberger location around the world, with the local influence making the remaining 25% both interesting and fascinating.

When transferring internationally to somewhere as different as Beijing, the work environment is not the primary challenge. As I mentioned above, a lot of things associated with work are the same so minor adaptation is required. However, it is much more challenging for the family, or what is known as “the trailing spouse.” We had been forewarned of this before the move as we invested a lot of time and effort to ensure the transfers worked out well. Indeed, within Schlumberger, the type of transfer that was often at most risk was for US people to move away from the US.

We were extremely blessed on arrival and during our stay by Jill and Sammy Gauthier, and their daughter Sydney who was Bailey’s age. Sammy was in Schlumberger sales and they had the genuine Cajun warmth from Louisiana. When we first arrived in our new apartment, they had stocked the fridge and made the beds. Bailey and Sydney were best friends for the year and we had many fine times together. Jill was a tremendous help to get Janet settled.