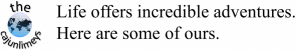

It was over thirty-five years since I had used the Royal Geographical Society (RGS)’s Expedition Advisory Centre to help me organize my first expedition to Egypt in 1989. I had been able to get assistance without visiting their facility in London’s South Kensington. I had also been a member of a university expedition to Venezuela the following year and participated in other expeditionary trips to Irian Jaya (Papua), Belize, and Idaho. I had felt a bond with this type of travel. When I was gainfully employed after graduating, the RGS presented to me the opportunity to become a Life Fellow, which I took, without understanding how I might use it. For over three decades, I did not. Just as an expedition requires a purpose to visit a location, I needed a purpose to visit the RGS, and it came from the most unexpected source.

Expedition Planning and Preparation

When planning an adventurous trip to England with friends from our current hometown of Houston, Texas, you can imagine my excitement when Max asked whether we’d be able to visit the RGS. He had recently watched The Lost City of Z, which describes Percy Fawcett’s exploration of South America, and had become fascinated with what exploration in the early 20th century had been like. All that Max was expecting was to walk past the RGS building, perhaps peeking through the door. I saw a very exciting opportunity to do more, yet the RGS’s Lee Rodrigues turned it into a visit of a lifetime, greatly exceeding our expectations.

A couple of months before our trip, I made enquiries about a visit and Lee Rodrigues from the RGS’s collections team responded promptly and thoroughly. He pointed me to online databases of their collections and I searched for everything associated with Fawcett and added them to my request form. I thought of this as “open research” investigating Fawcett’s explorations. I was unsure where it would go. Max and I also noted that the material titles suggested his wife, Nina Fawcett, played a significant role, which we wanted to understand more. To my request I added the reports from my university expeditions to Egypt and Venezuela. With everything lined up, we completed the other activities of our England adventure, and undertook our expedition to the RGS on our final day in London.

Below I describe our tour of the RGS facility, summarize our analysis of the material on Fawcett (artifacts, photos, maps, and letters), recap my expedition reports, and reflect on the visit which includes thoughts on what an “expedition” is!

A Tour of 1 Kensington Gore

One highlight of our visit was a personal tour by Lee Rodrigues of the RGS’s rooms, especially those that are closed to the public but open to members and fellows. The RGS purchased Lowther Lodge in 1913 with one extension built in 1930 and another opened in 2004. The society describes their buildings and history in this publication. Below is my brief description using the photos I took with my iPhone. This article by Ashley Giordano in July 2024 gives a more formal overview.

Lord Shackleton is Edward, younger son of the famous explorer Ernest, who received a special gold medal in recognition of his service to geography and the society.

As we passed into the original 1913 building, past the “No Entry” sign indicating it was only accessible to members and fellows, we entered a short hallway that I will call the Livingstone nook. We had noted Livingstone’s statue on the building’s outside wall as we arrived, but this little exhibit inside was extraordinary. When the missionary explorer David Livingstone died in Africa in 1873, his heart was buried beneath a tree in Africa while his body returned to England, as per his request. A commemorative inscription was carved into the tree. When the tree died, the section with the inscription was brought to the RGS and is on display. The wood contains Livingstone’s heart!

Opposite Livingstone’s heart is this lift from the original Lowther Lodge. It is the oldest working lift in a private home in London.

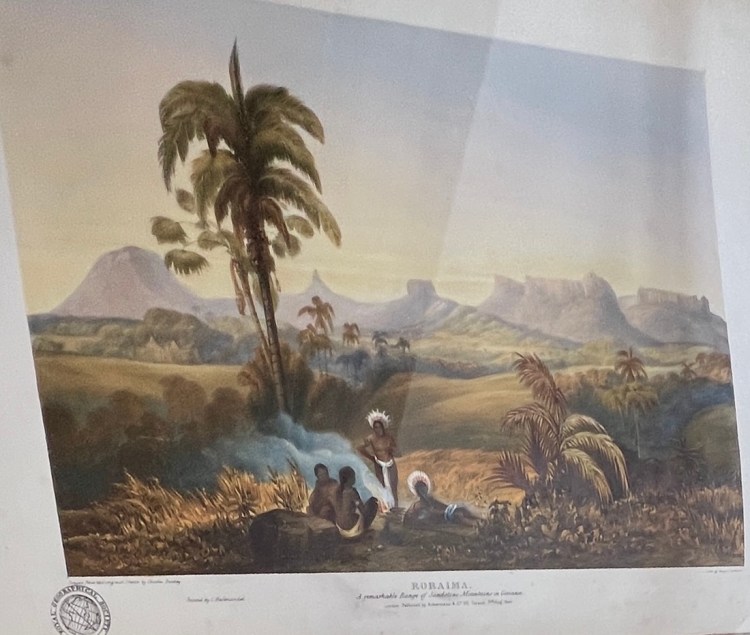

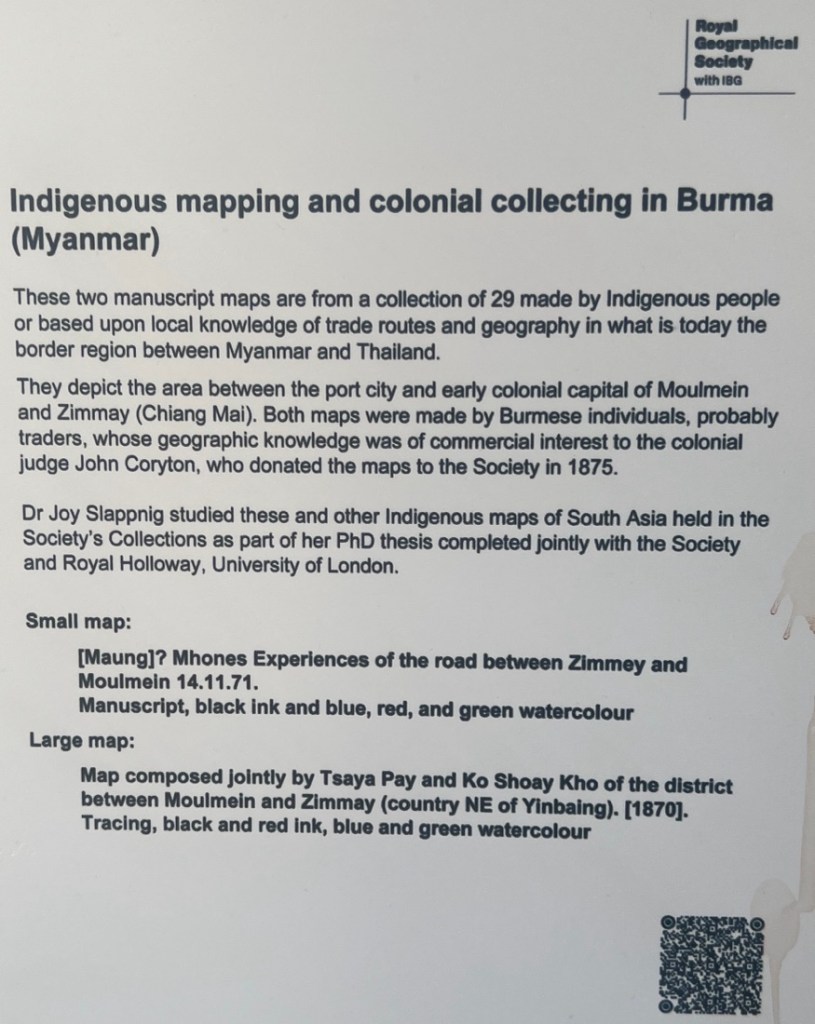

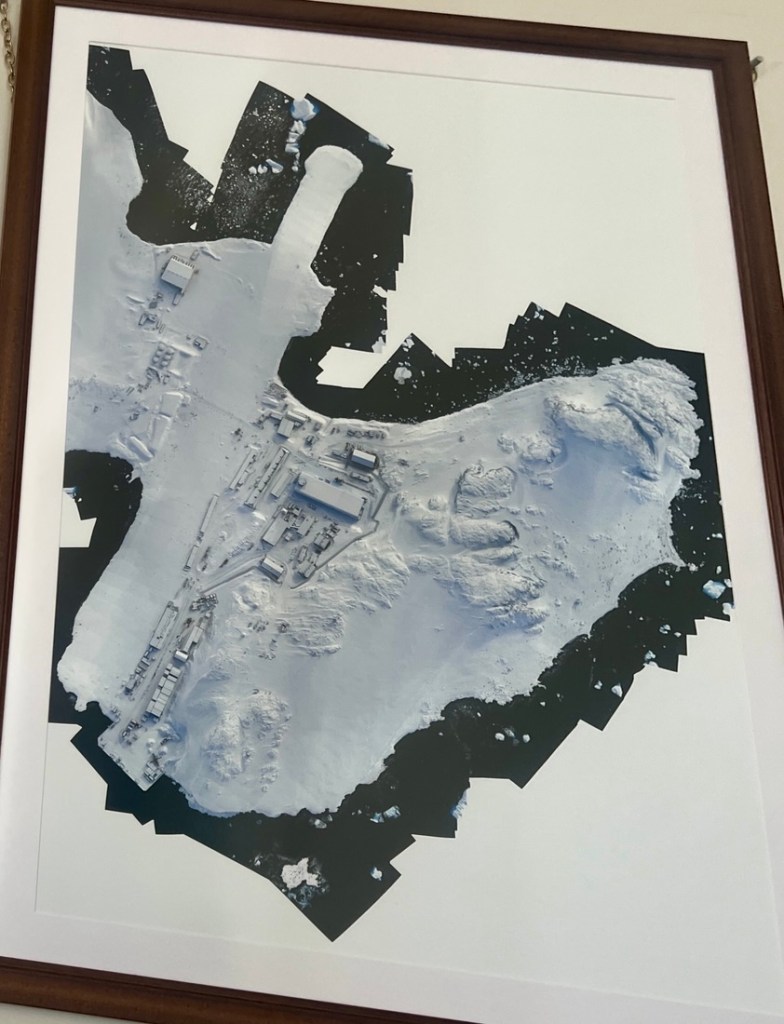

Next was the Map Room. While the vast majority of maps are stored in the climate-controlled archive off the Foyle Reading Room, the room retained some fascinating artifacts.

Why is it still hanging on the wall? Lee explained that uncertainty about how the map was mounted and hung prevented it from being removed due to fear of damage!

Next, we entered the main hall with its creaky floorboards.

Off the Main Hall was the Everest Room.

Also off the main hall is the old main entrance.

Most of our visit was spent in the Foyle Reading Room, part of the most recent extension.

Visiting the RGS facility was a fantastic experience.

Fawcett – An Overview

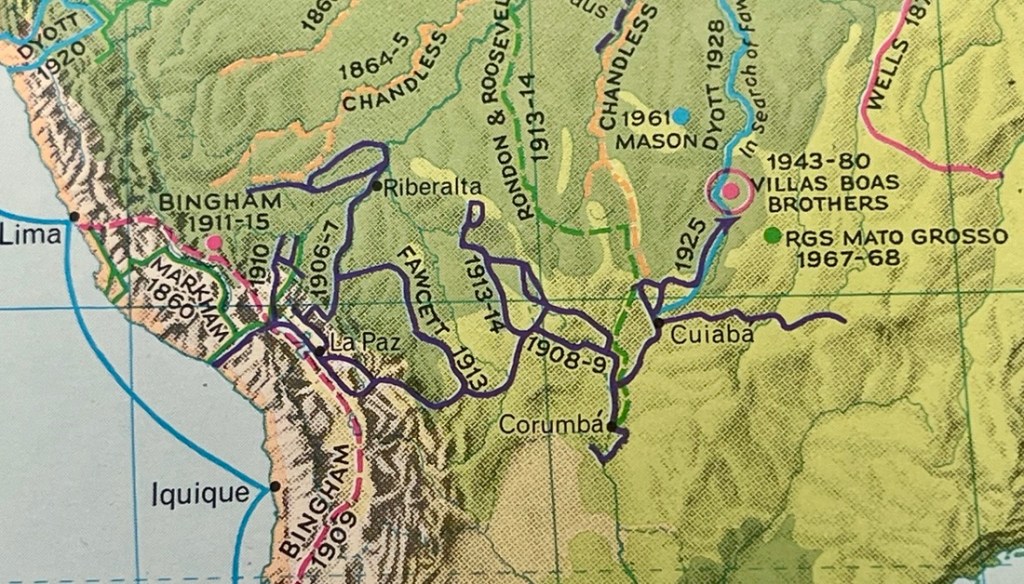

Most of our visit was researching Percy Fawcett. Who was he? Born in 1867, he joined the Royal Artillery in 1886 and served in Hong Kong, Malta, Trincomalee, and Ceylon. In 1901, he married Nina Paterson. In the same year, he joined the Royal Geographical Society to further his knowledge of surveying and mapmaking and worked for the British Secret Service in North Africa. During his service, he befriended Arthur Conan Doyle who used Fawcett’s field reports as inspiration for his novel, The Lost World. In 1906, he led his first expedition to South America on behalf of the RGS who had been asked by the Bolivian government to map an area of jungle on the Bolivia/Brazil border. This was the first of seven expeditions Fawcett made between 1906 and 1924. When the First World War broke out, he volunteered for duty in Flanders, despite being nearly fifty years old, and received several commendations. In 1924, Fawcett returned to Brazil with his son Jack and Jack’s friend Raleigh Rimmel in search of a lost city that he believed to exist and that he named “Z” (Zed). Fawcett’s last communication was a letter he wrote to his wife Nina on 29 May 1925. In January 1927, the RGS officially declared the three men lost. Many volunteer expeditions attempting to find Fawcett failed. David Grann tells Fawcett’s story in his 2009 book, The Lost City of Z, which was made into a feature film in 2016. Some argue that the Indiana Jones character is based on Fawcett.

While it was possible to read and watch books and films about Fawcett, our examination of primary materials gave us unique insights into Fawcett, his wife Nina, their interaction with the RGS, and the challenges his expeditions faced.

Fawcett’s Artefacts

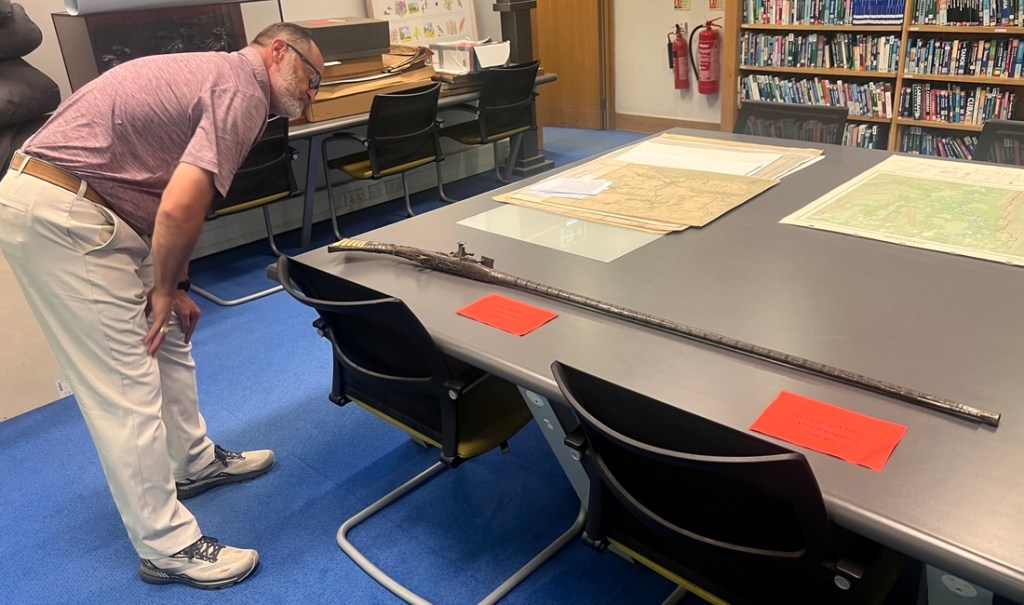

From the online catalogs, I identified two artefacts relevant to Fawcett. The first was a jezail, described as an “ivory and silver decorated snaphaunce musket from Morocco.” Fawcett likely acquired it there in the early 1900s, though the gun was manufactured long before that. Its ornateness suggests it was used for hunting game rather than for battles. Fawcett did not take it to South America.

The second artefact was an aneroid, a barometer that showed atmospheric pressure and altitude. It was used for weather forecasting and navigation.

The RGS used to have a museum and this aneroid was one of the exhibits.

Lee had an interesting background, coming from Washington D.C. and working at other London museums before the RGS. His insight helped me understand the value of historical collections like the RGS’s and the criticality of organization and preservation. Many other historical collections have been damaged by flooding, fire, or excess humidity.

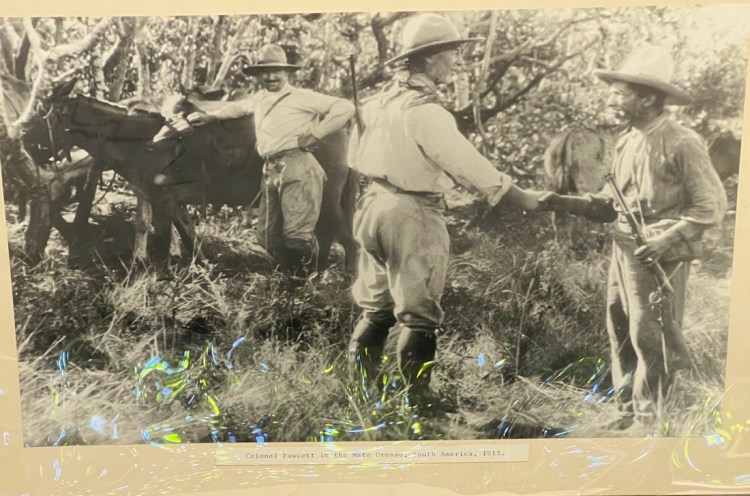

As well as the above artefacts, the collections catalog listed seven photographs pertinent to Fawcett. Without deeper research to place them in context, they were difficult to interpret. This one was the most interesting.

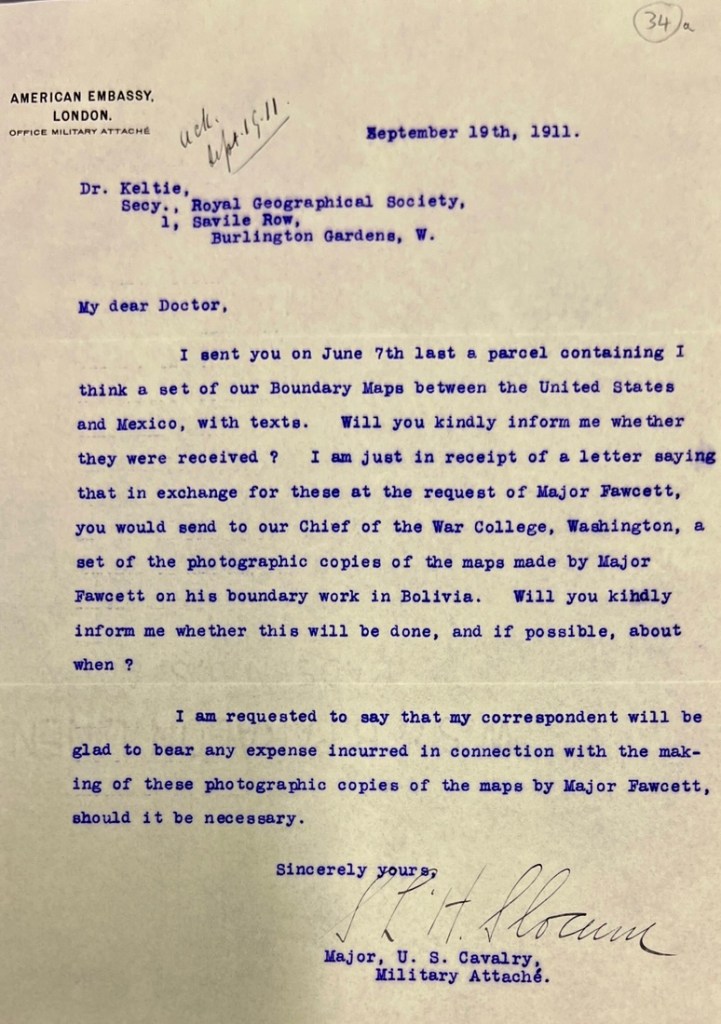

Fawcett’s Maps

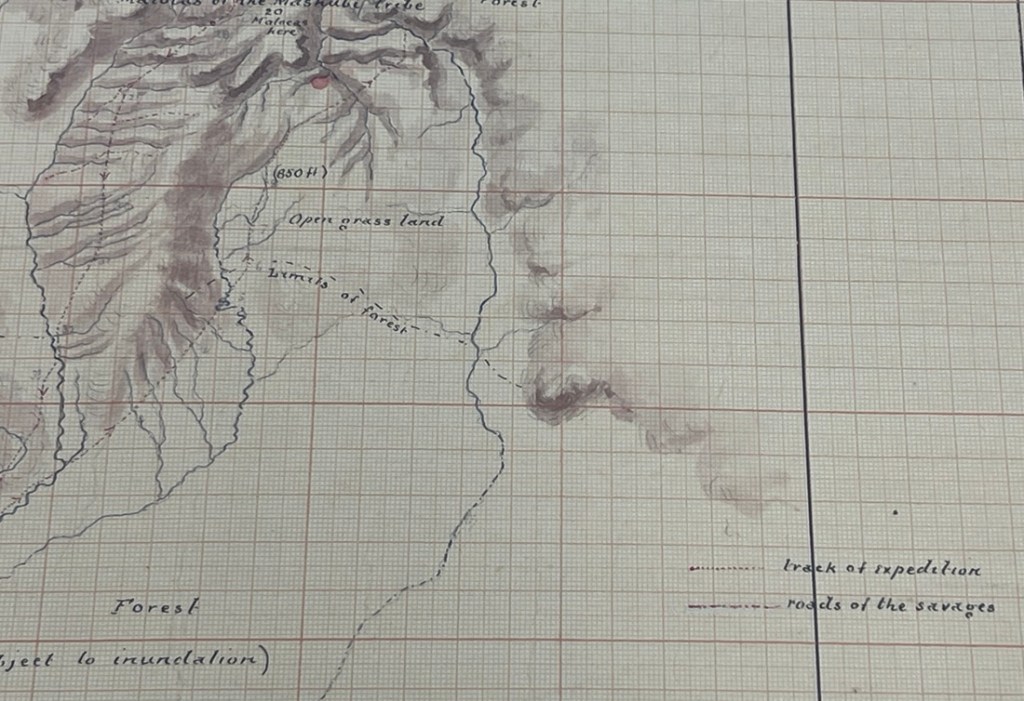

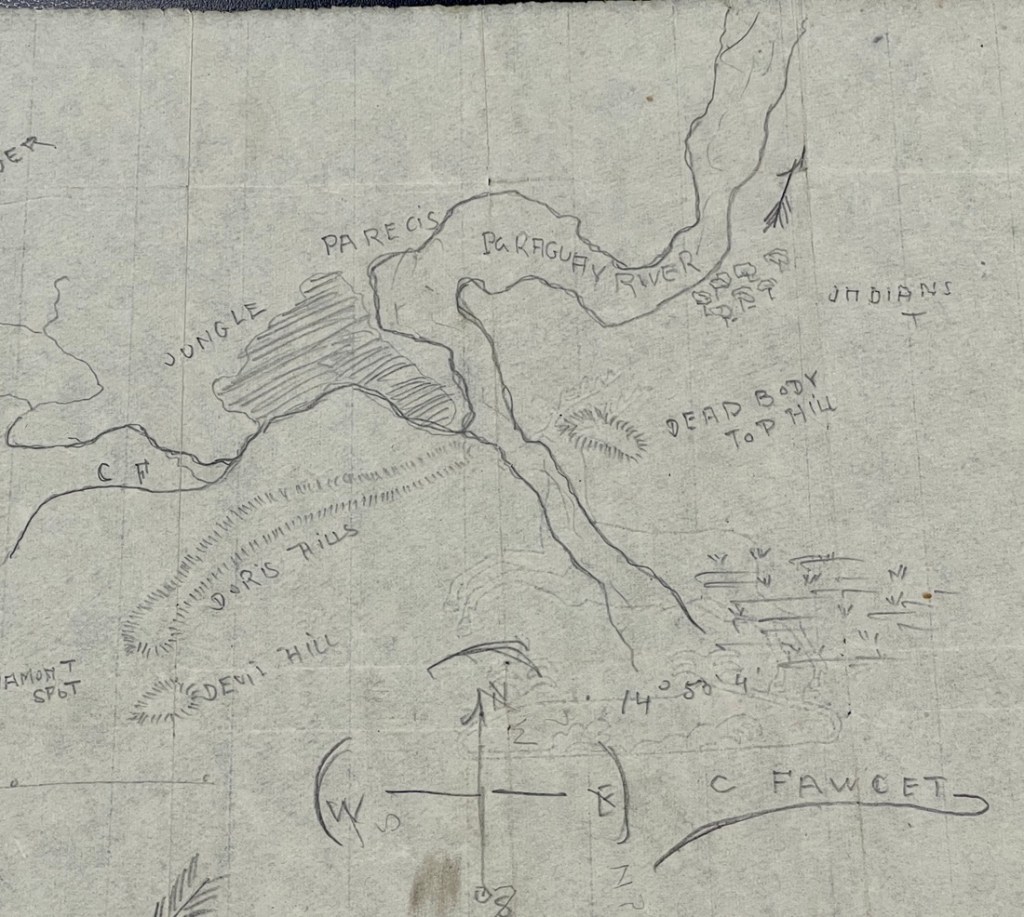

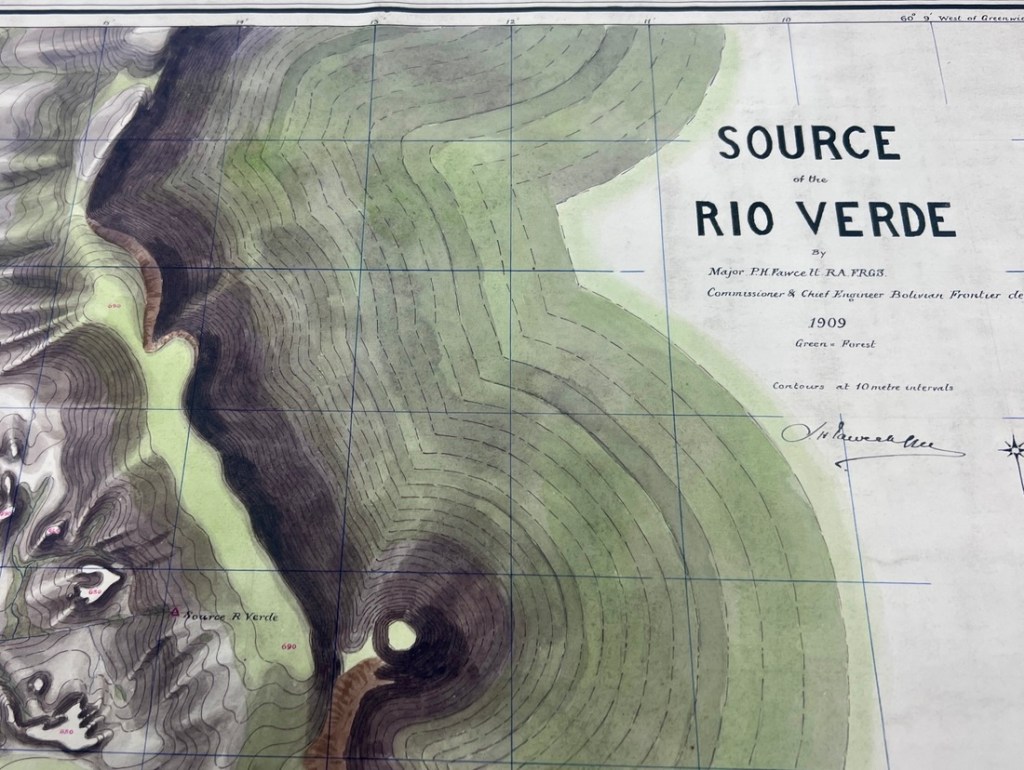

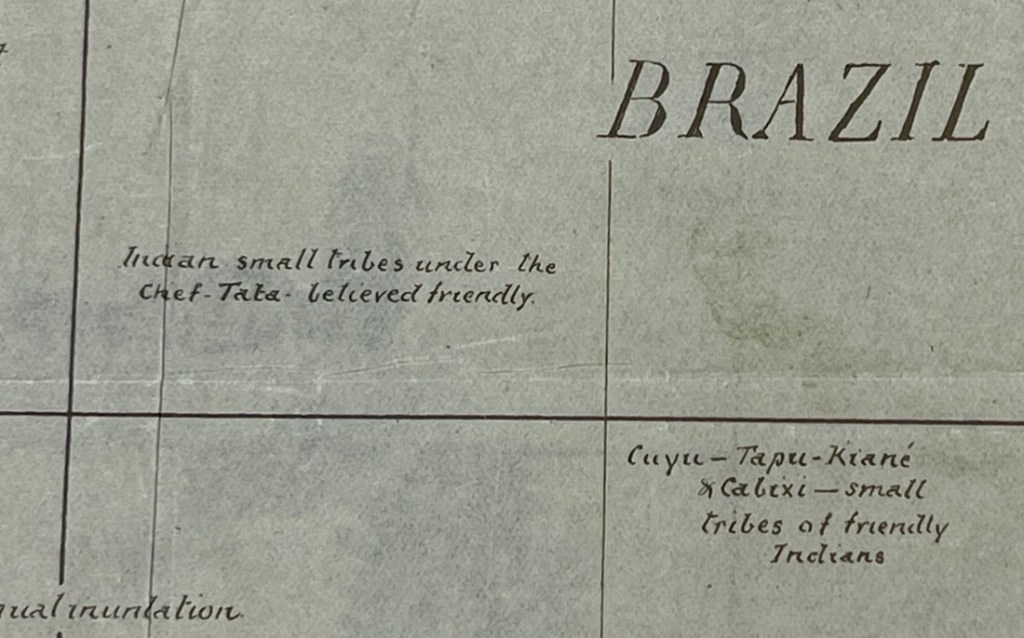

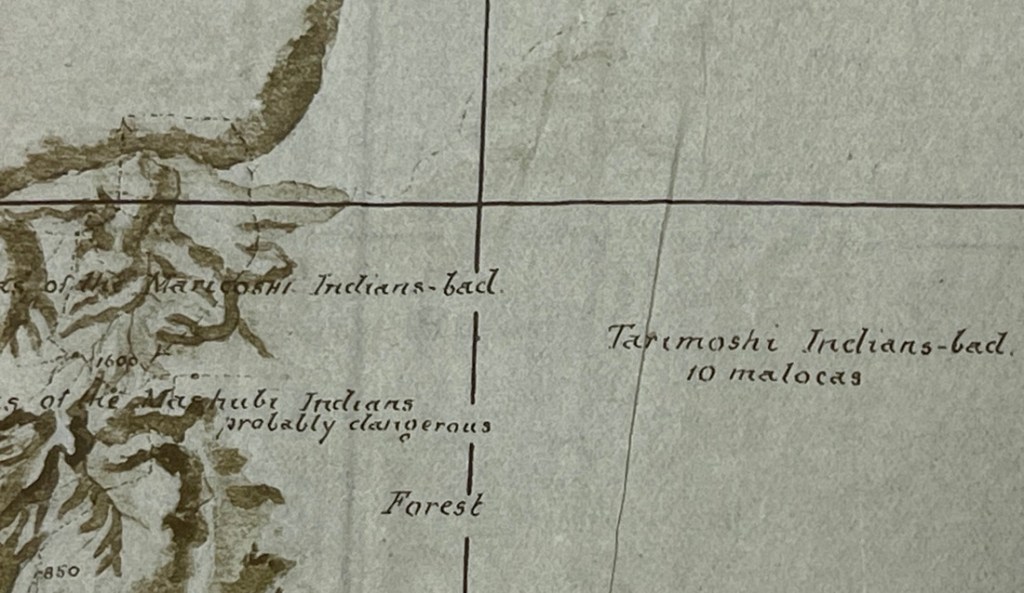

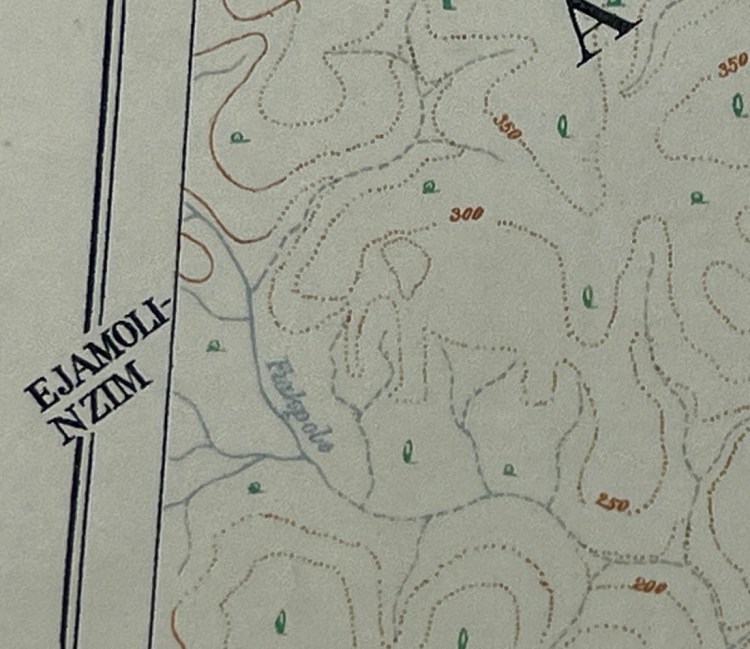

We examined the maps that I had requested, and it quickly became overwhelming. There were multiple collections of several maps and it would have taken significant time just to locate the areas that each map was describing. However, it was fun and fascinating to carefully review them and they provided some insight into Fawcett’s mapping work.

He described villages by the number of “maloca” which were large communal traditional dwellings.

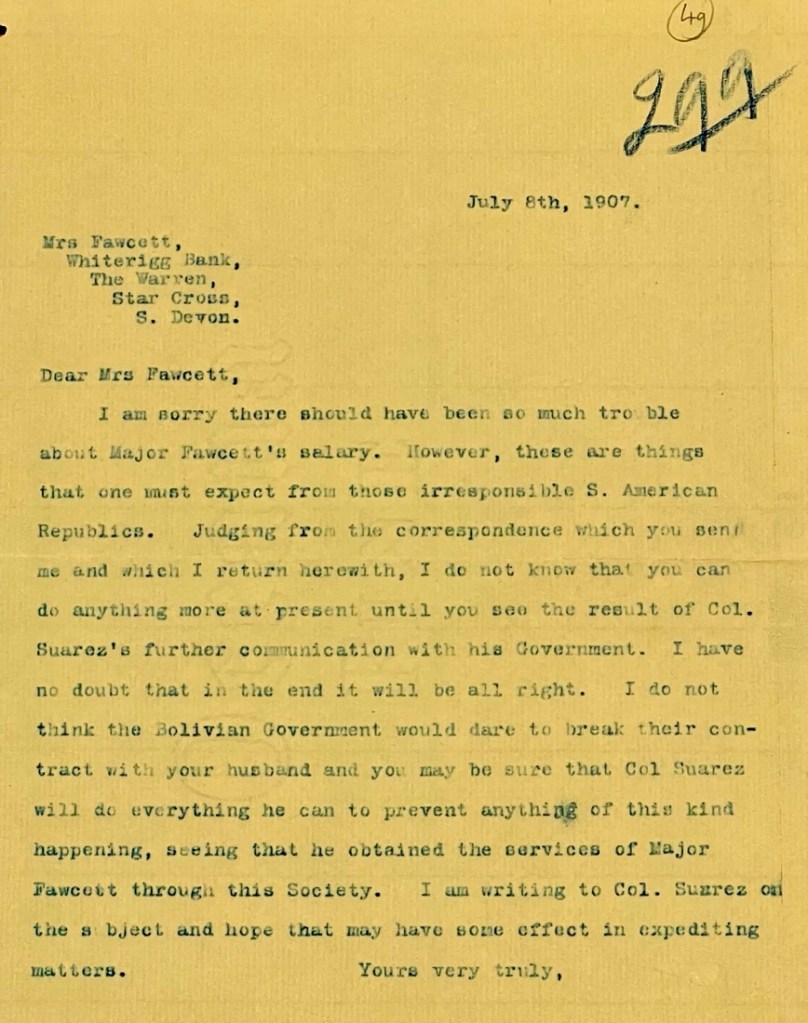

Letters

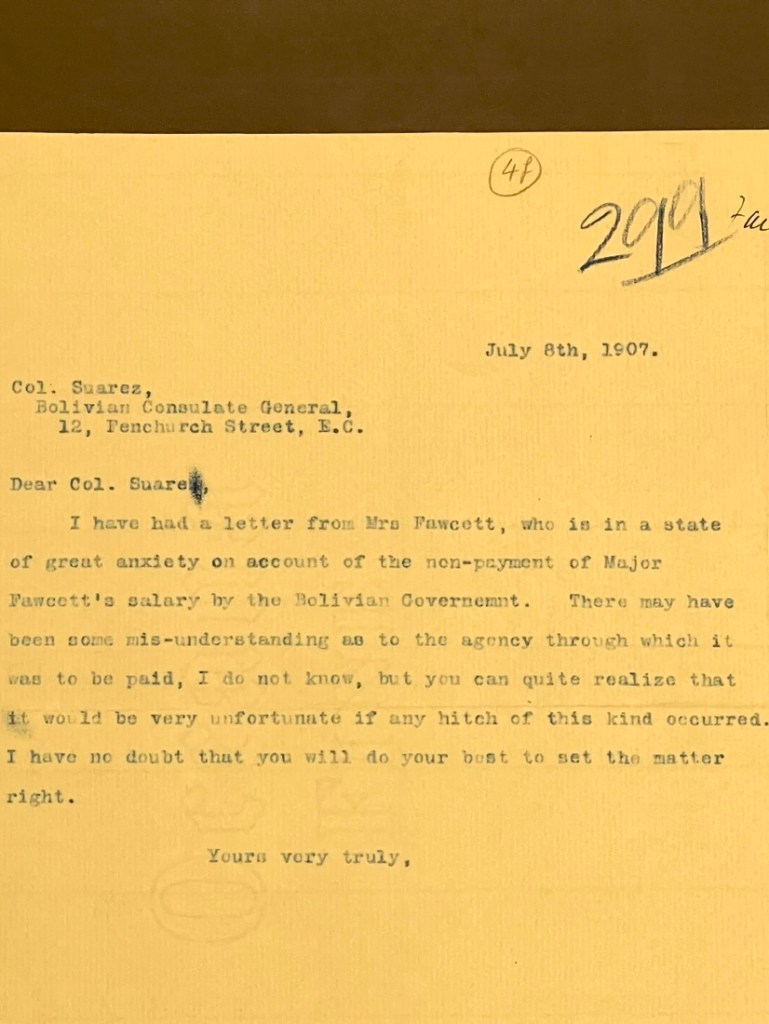

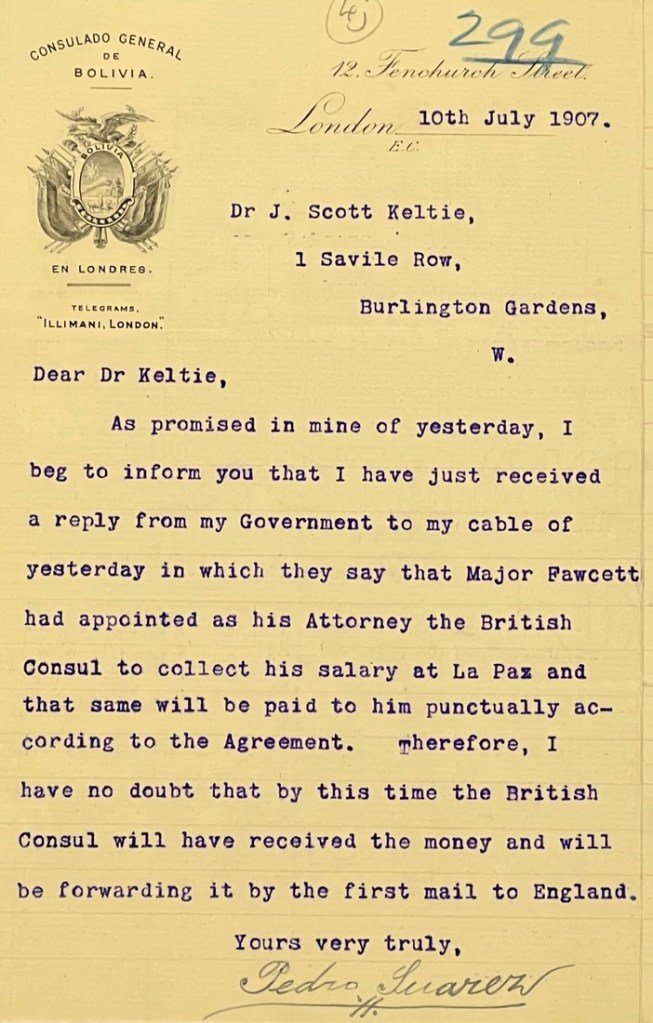

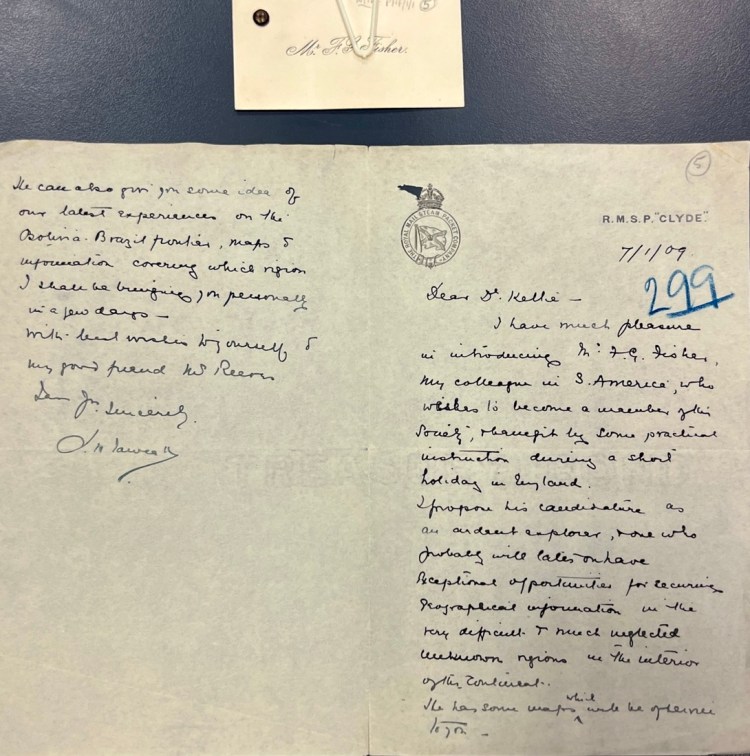

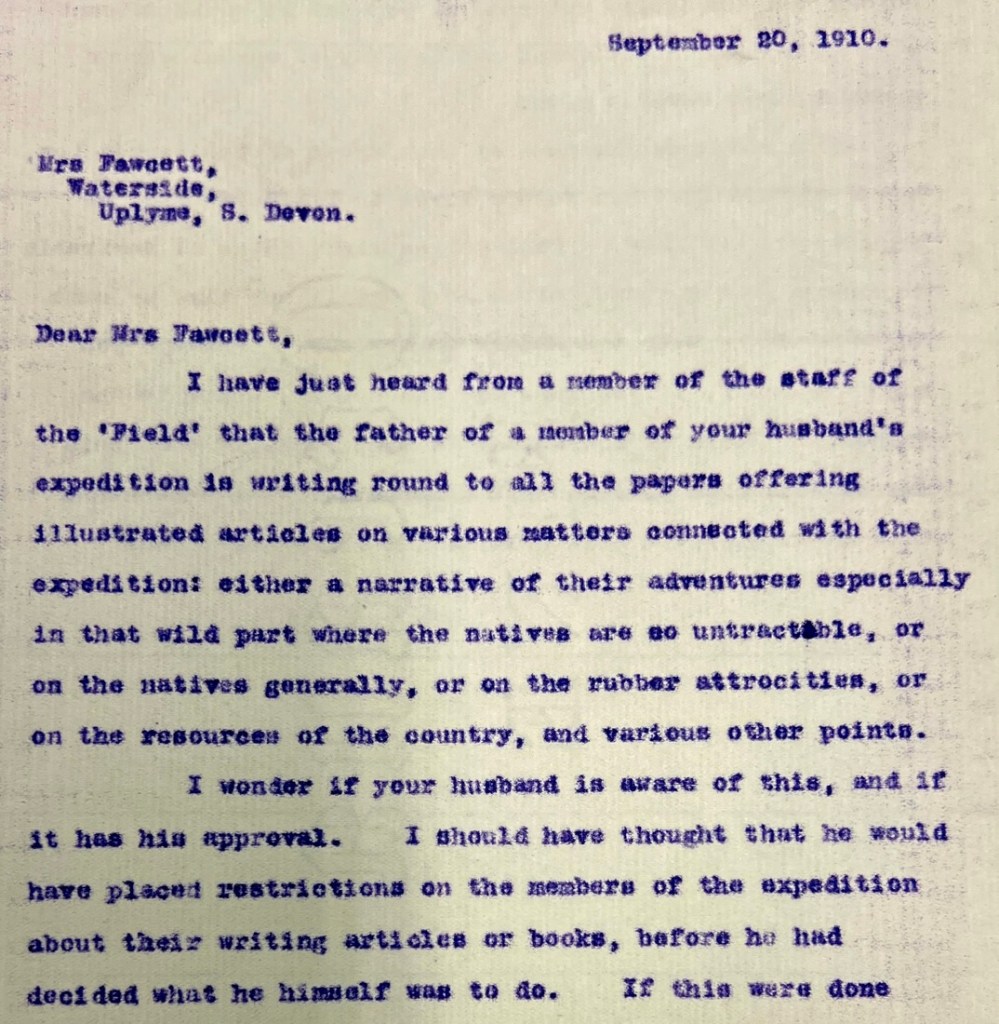

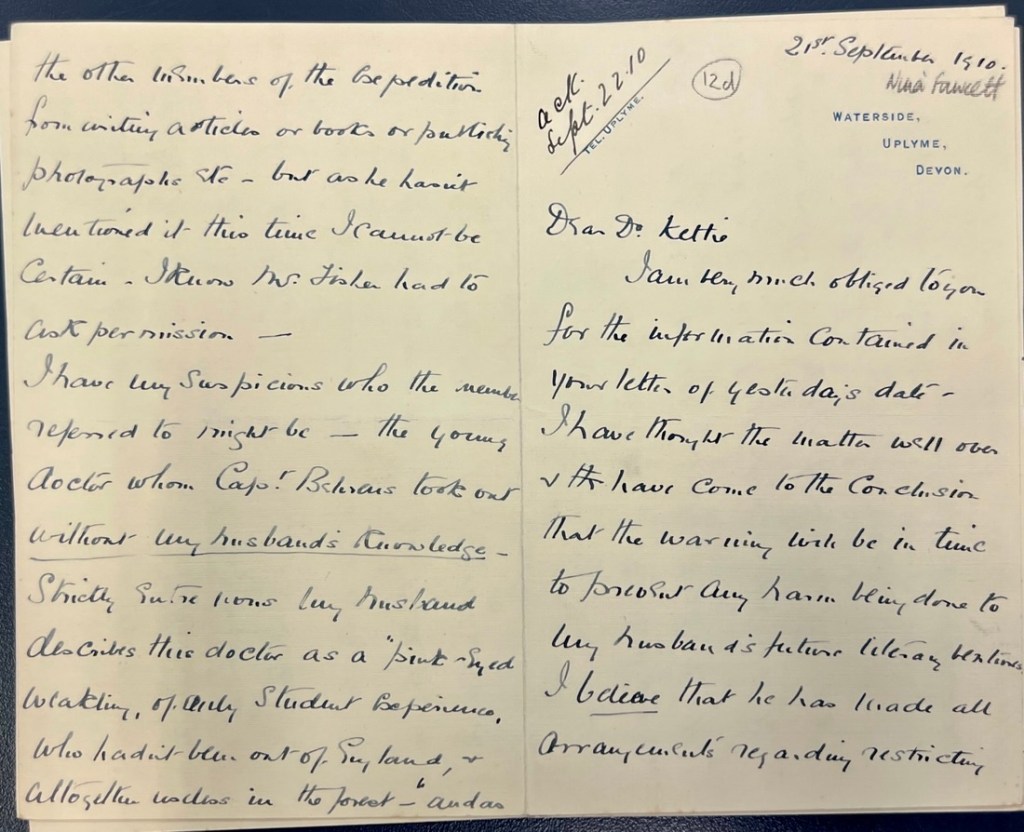

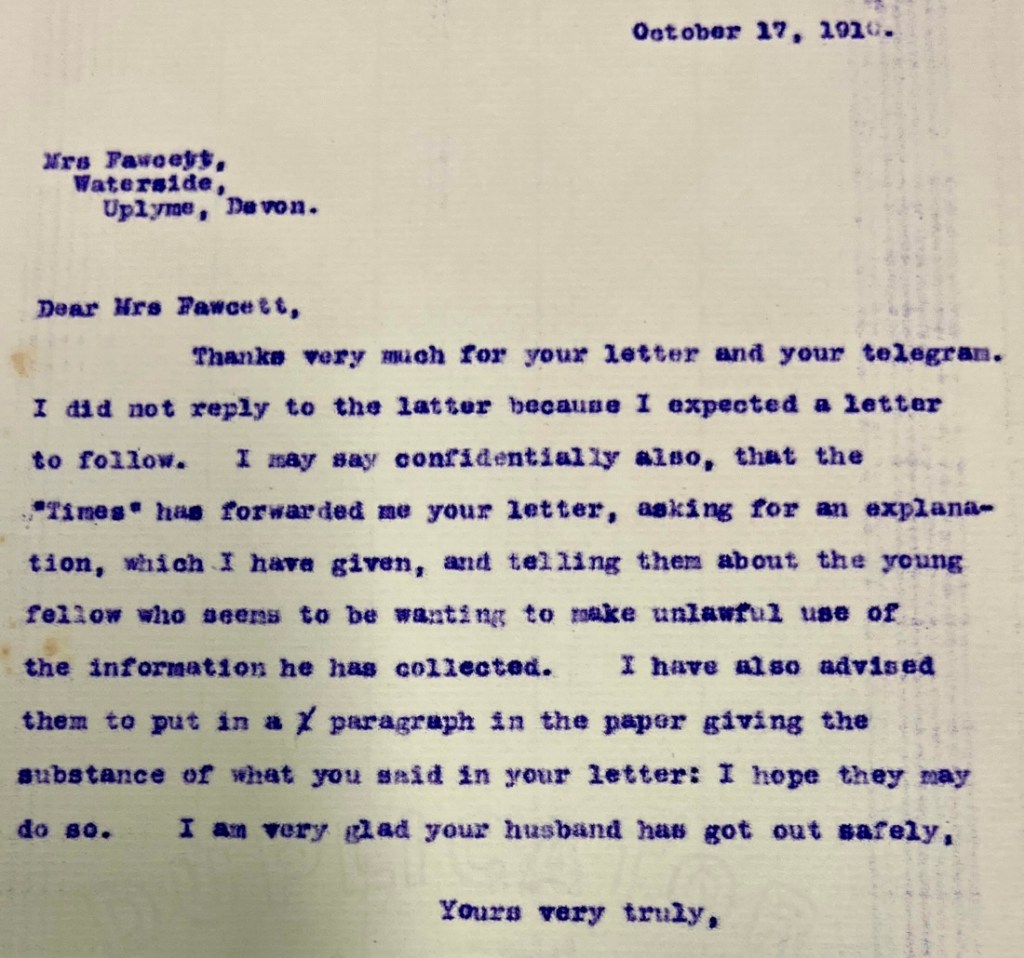

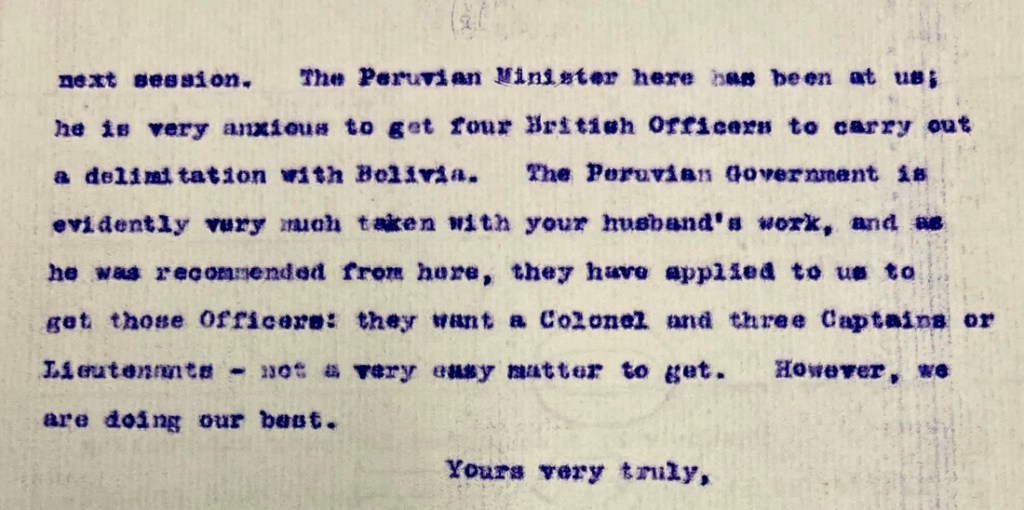

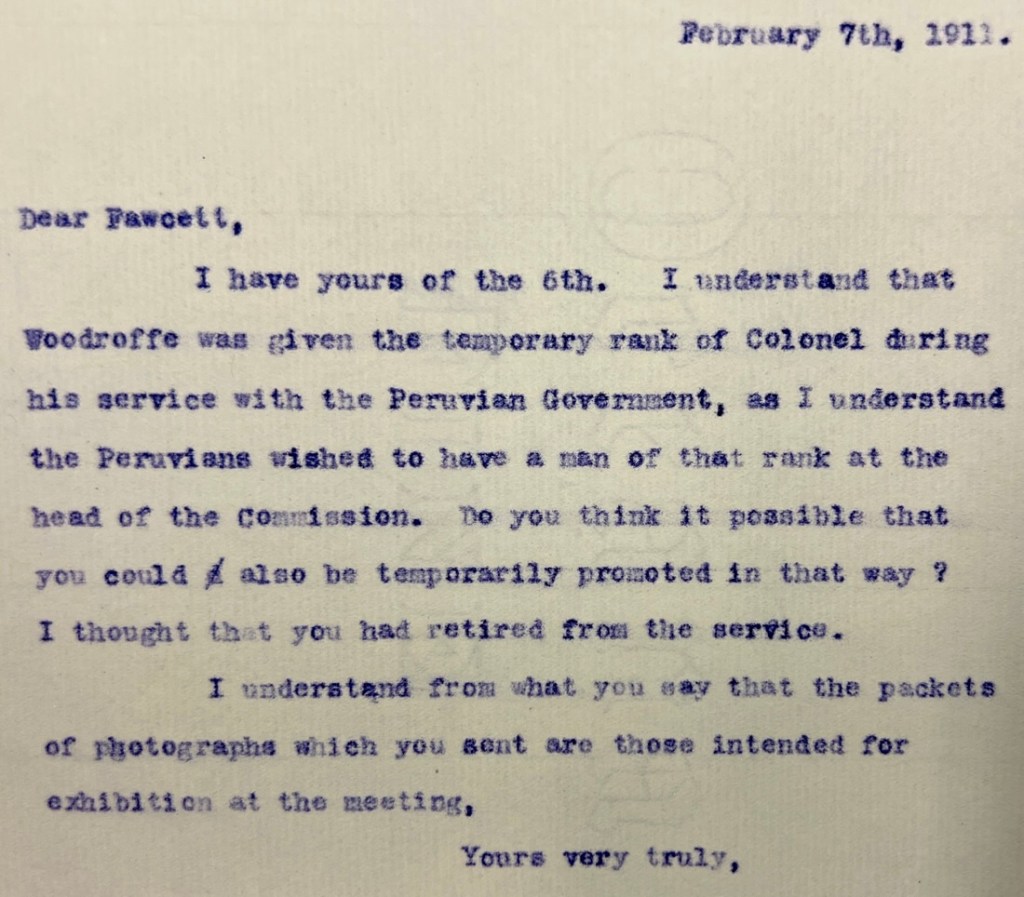

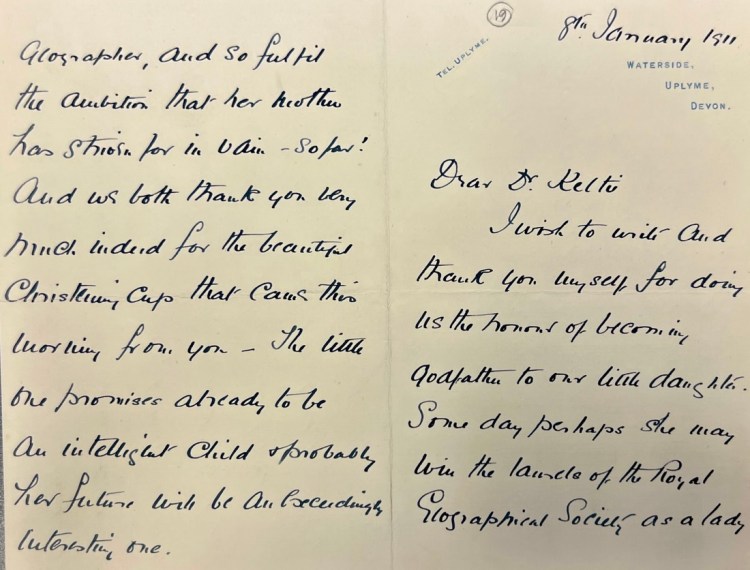

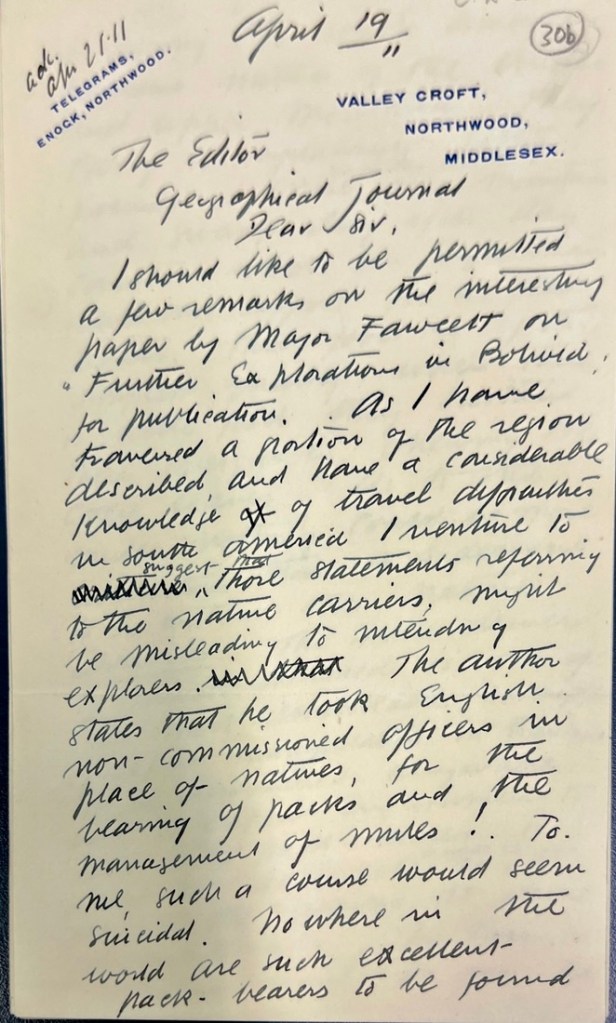

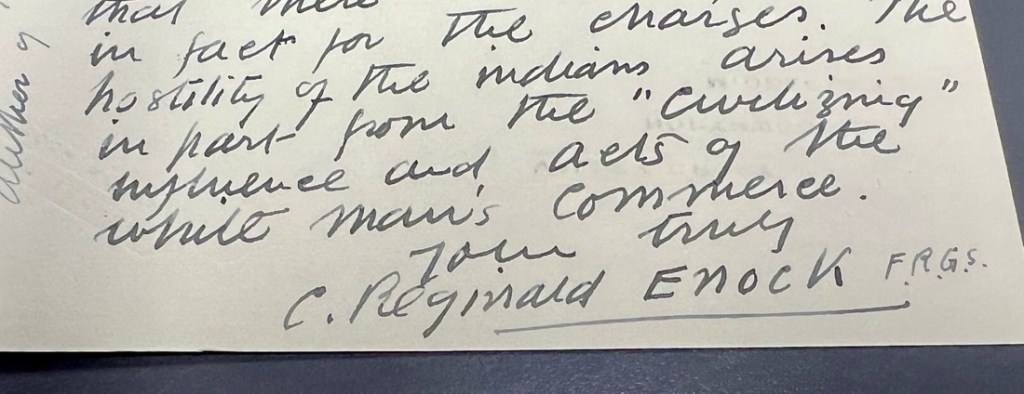

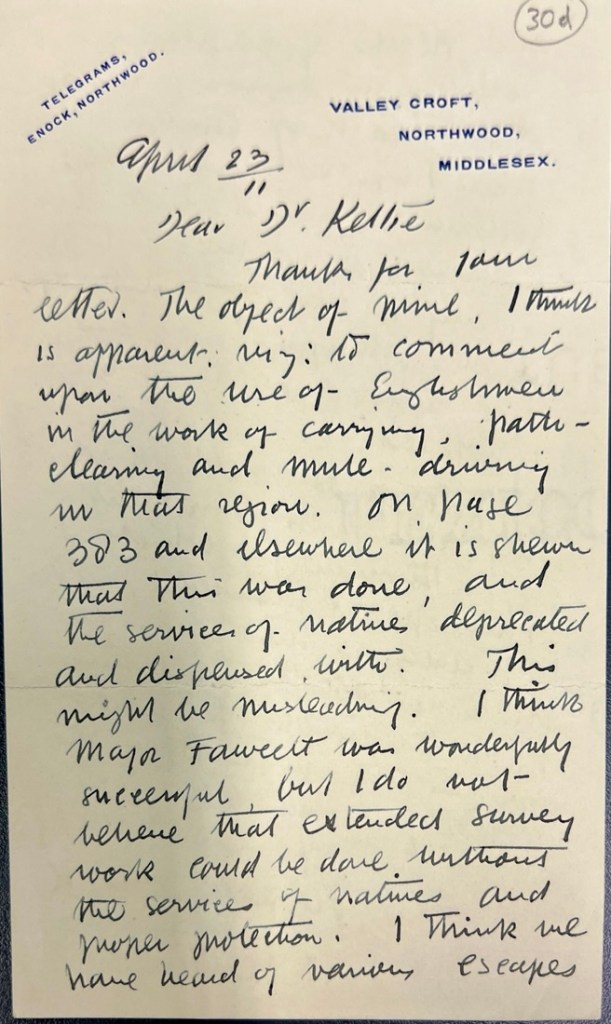

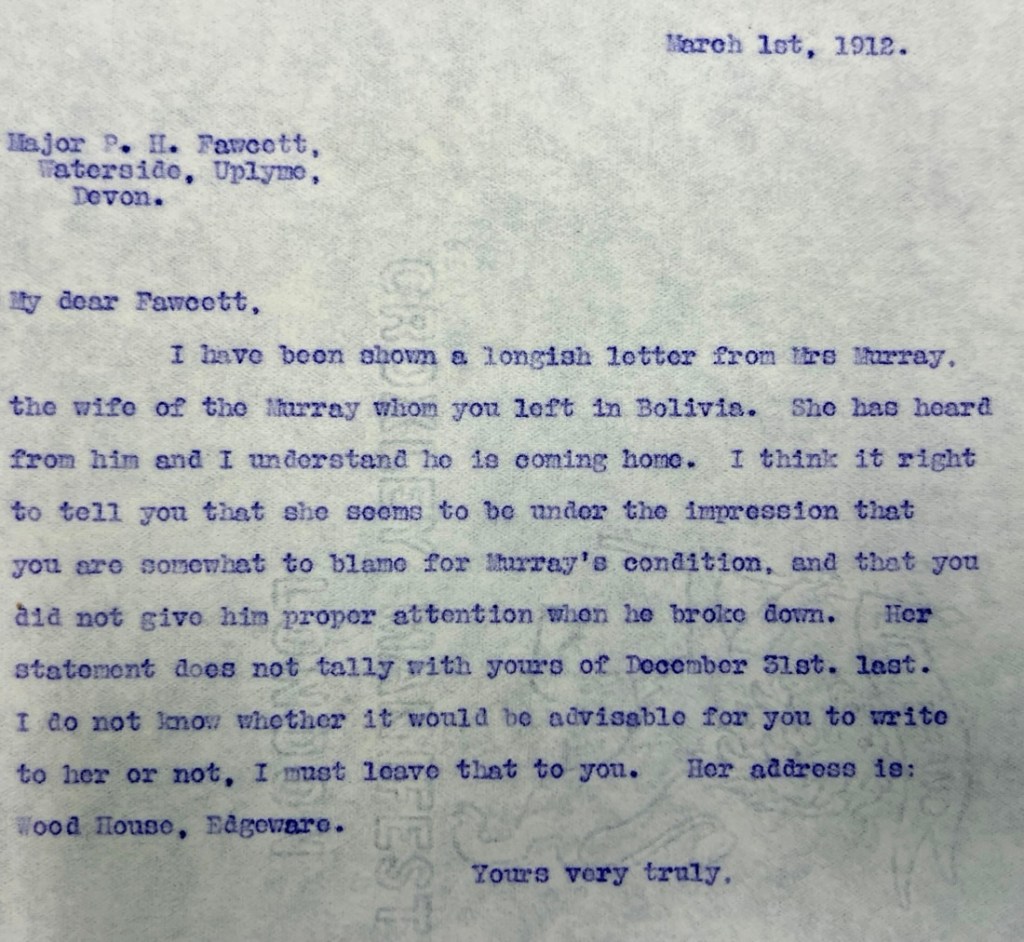

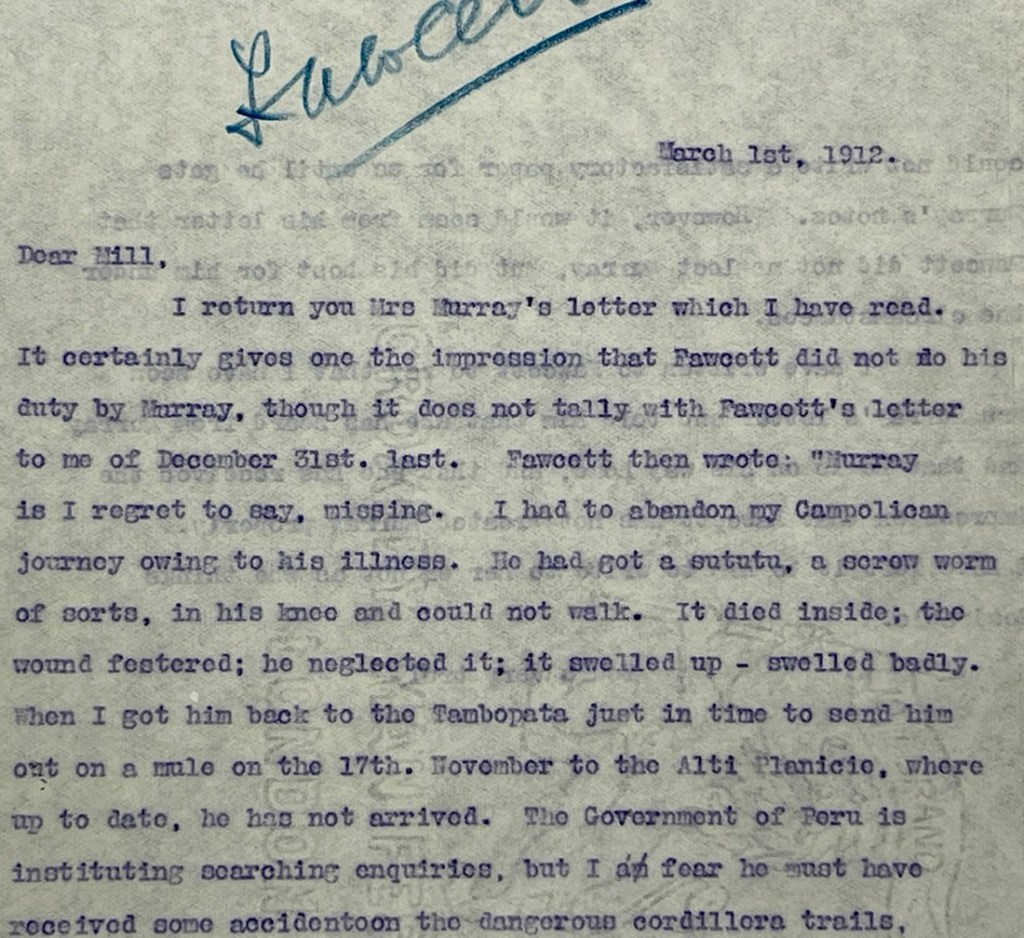

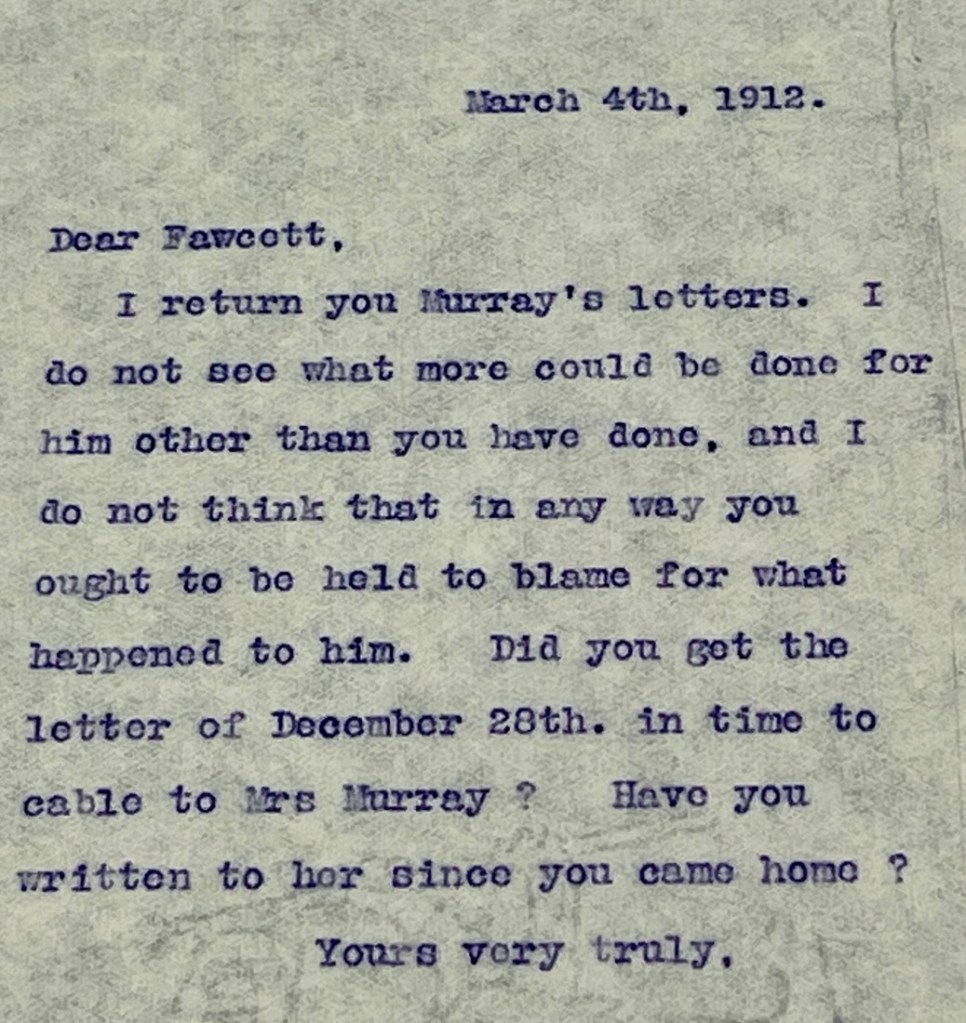

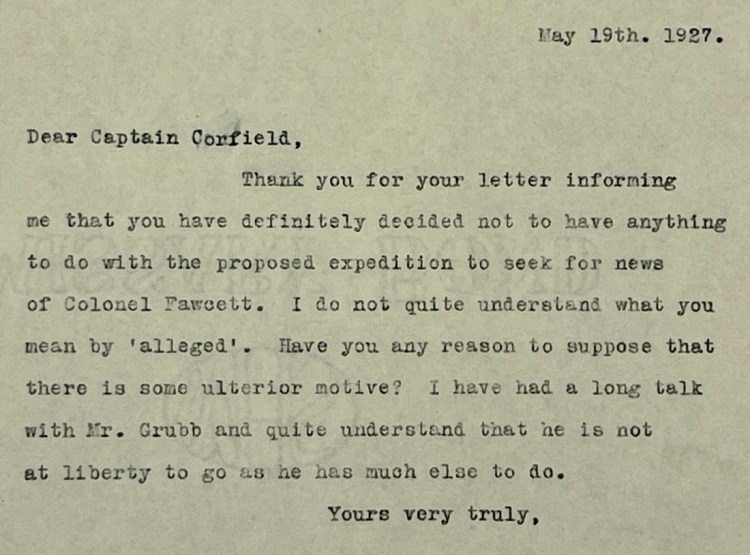

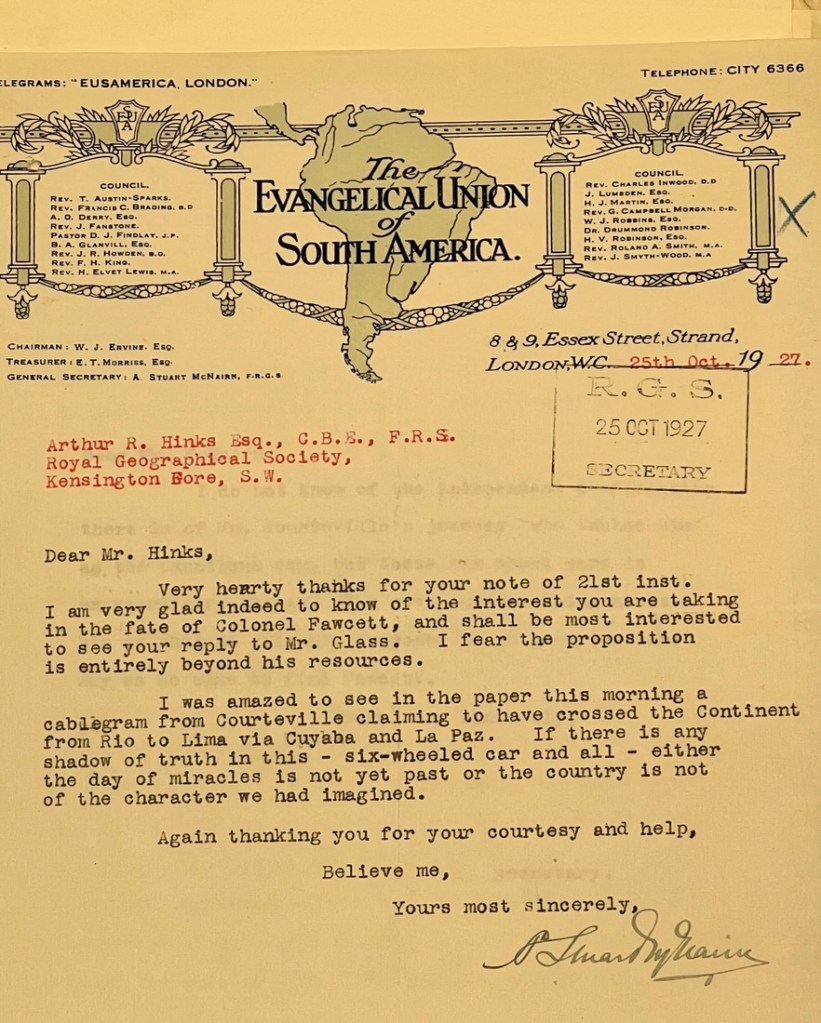

Within the online catalog was the entry “The Fawcett Collection.” This comprised of over thirty folders of correspondence and various other documents. We selected a small sample, and quickly found even that overwhelming. Most of what we reviewed was correspondence to and from Dr John Keltie, the society’s secretary, that was pertinent to Fawcett between March 1906, when the RGS invited Fawcett to lead a survey of the boundary between Bolivia and Brazil, and March 1912, when we stopped due to pending exhaustion. The collection included letters that the RGS had received and carbon copies of the typed responses that Keltie had sent. Trying to decipher handwritten letters was very challenging. We also reviewed correspondence from 1927 after the RGS had officially declared Fawcett missing.

It was sent from the RGS’s address at 1 Saville Row.

Keltie asks Fawcett whether a temporary promotion to that rank would be possible for him.

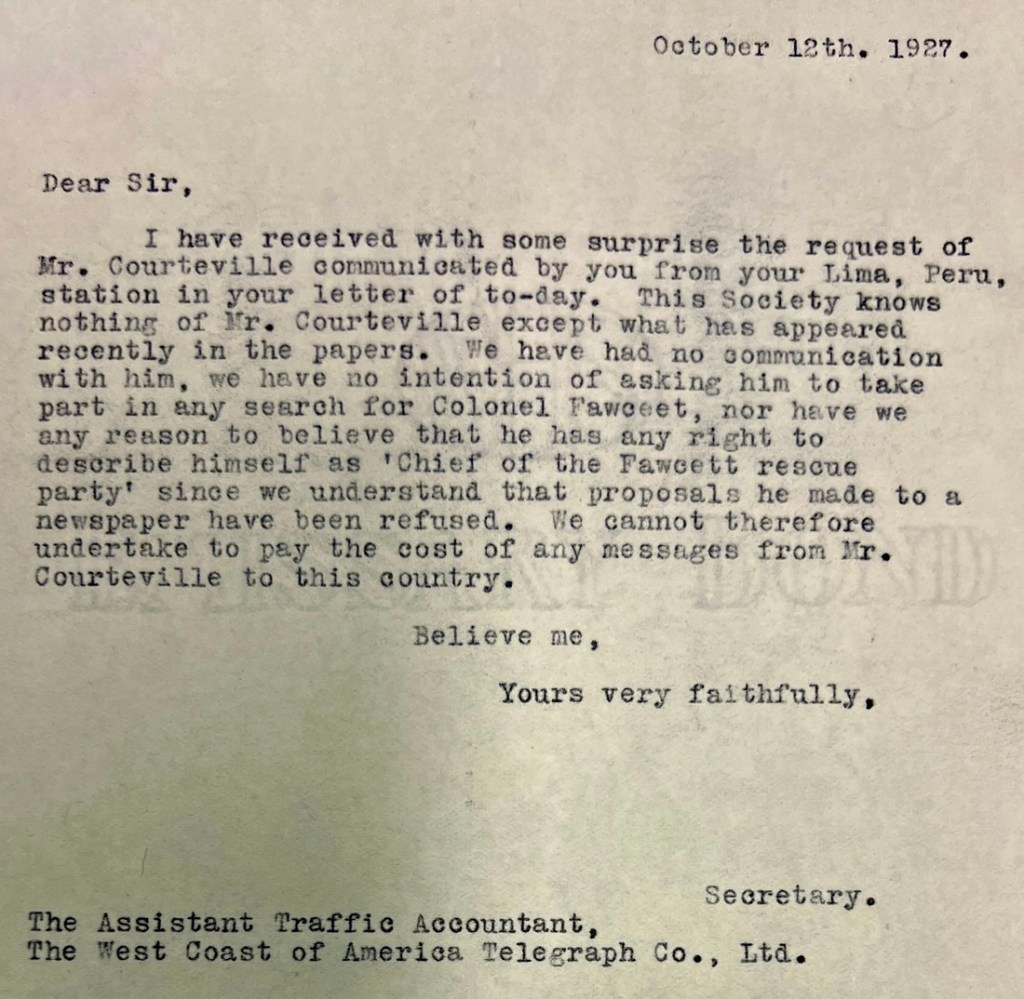

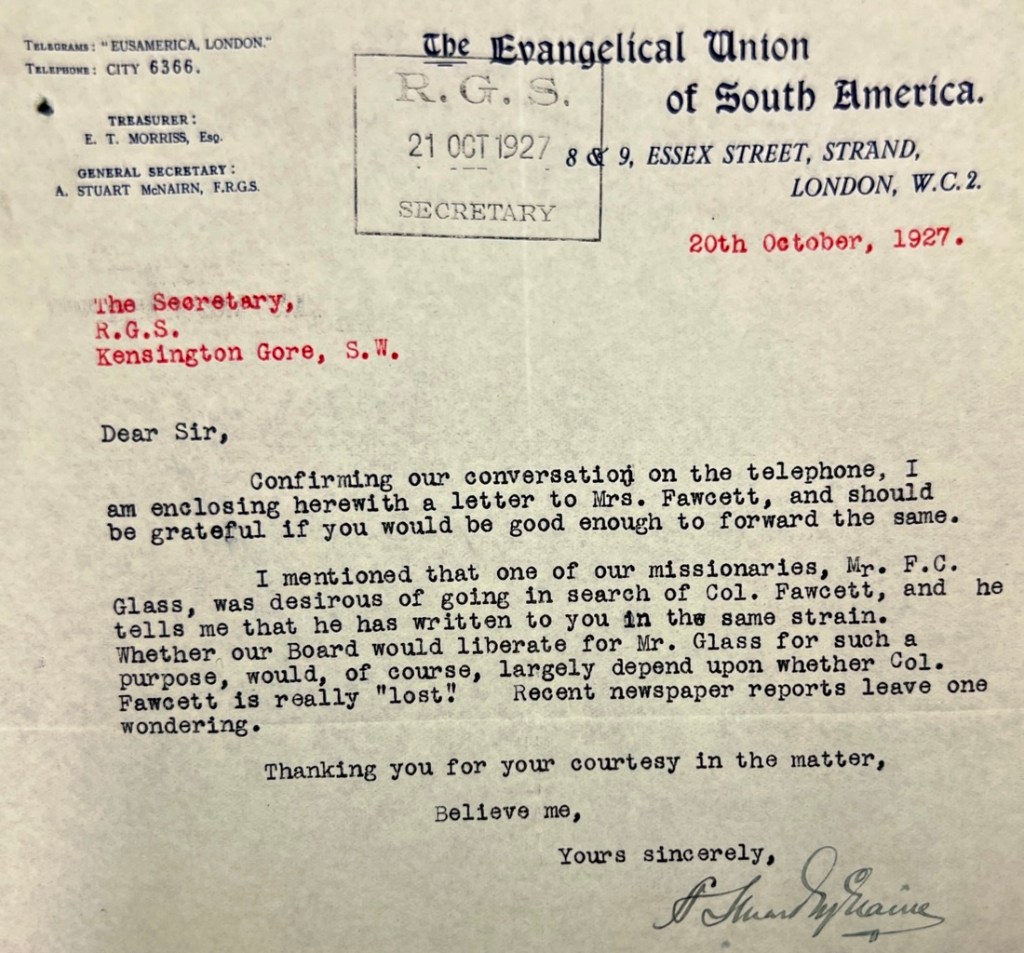

Our research skipped forward fifteen years due to lack of time and energy. We got some insight into the activities that occurred after the RGS declared Fawcett lost in January 1927, over a year after his last communication in May 1925.

Courteville claimed that he had found Fawcett.

“I was amazed to see in the paper this morning a cablegram from Courteville claiming to have crossed the Continent from Rio to Lima via Cuyaba and La Paz. If there is any shadow of truth in this – six-wheeled car and all – either the day of miracles is not yet past or the country is not of the character we had imagined.”

This was a beautiful way for an evangelist to call someone a liar and describe their tale as utter hogwash!

Our short review of Fawcett’s material had been fascinating and insightful. The correspondence revealed the mundane issues that faced his expeditions while communication was better than I expected. Much of Fawcett’s communication with the RGS when he was in the field went through his wife, Nina, who appears to be very supportive. It must have been difficult for her when he was away for months at a time, and I cannot imagine her challenges when Fawcett’s letters stopped in 1925 and he was declared lost in 1927 with their son.

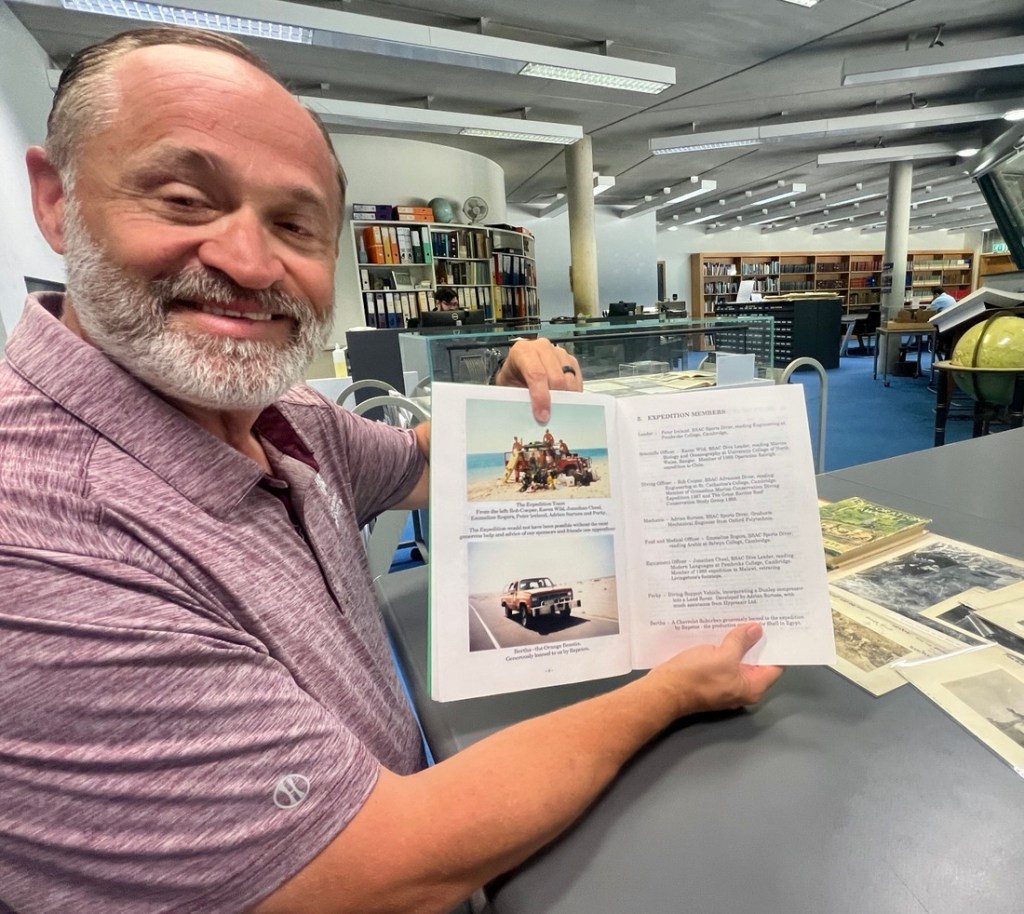

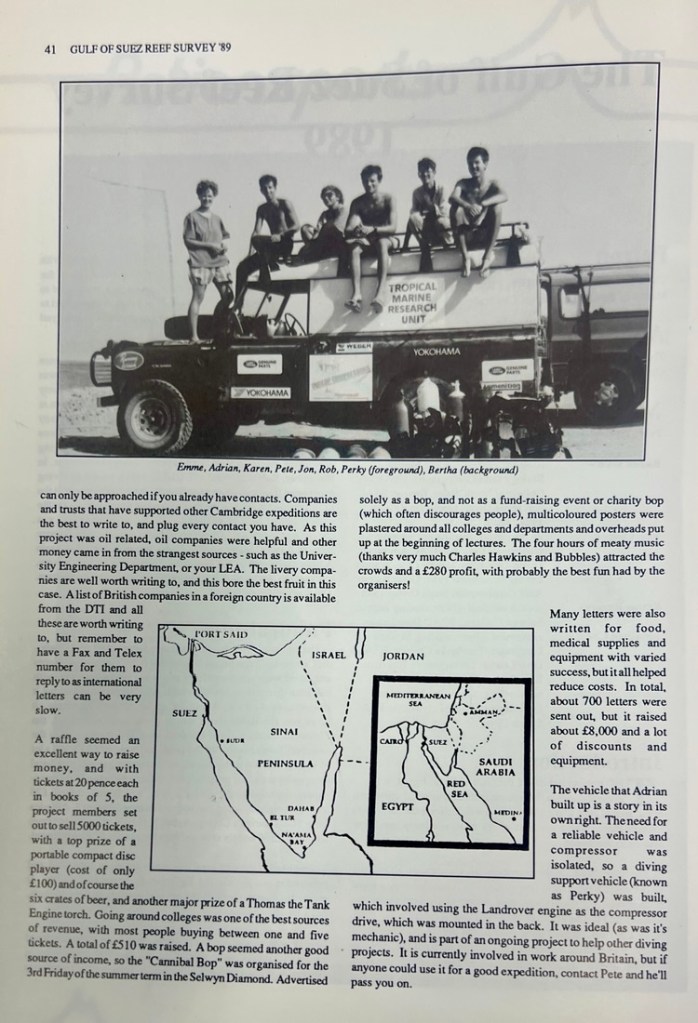

A Review of My Reports

While we were in the RGS, I wanted to show Max my expedition reports. I authored the report from the Gulf of Suez Reef Survey 1989 and had contributed to the report of the Cambridge Columbus Botanical Study Venezuela 1990. We noted that the RGS’s online catalog did not include digitized copies of these reports so I offered them my copies.

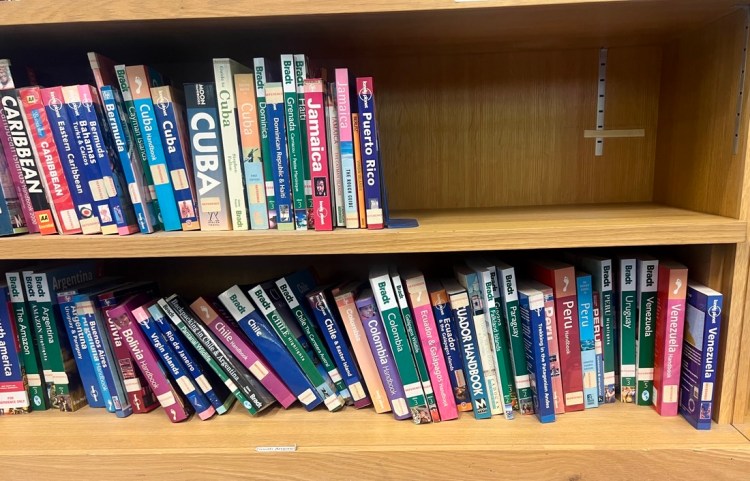

While reviewing these reports in the Foyle Reading Room, I looked up at the bookshelf and saw many Bradt travel guides. Excitedly, I saw “Venezuela” on the bookshelf and realized that it was the fifth edition which I had not previously seen. I had contributed to the first edition of the book. Even more excitedly, I turned to pp 274-275 where my description of Climbing Auyantepui remained. It was also very exciting to learn that a 1995 expedition by the Cambridge University Officer Training Corp had created a trail across the tepui to Angel Falls, with their route continuing from the route I had described.

The discovery led to discussions of other adventures. I mentioned that during another expedition to Irian Jaya (Papua) in 1992 that I was part of a group that had “moved a mountain.” Using a very early GPS, we had discovered that the local topographical map was wrong. The story lit up Lee’s face, and he quickly went to his desk to grab a 1923 map of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and told us the story behind it. The map was the work of a British surveying expedition. They had nearly finished the map, and one particularly inaccessible hill remained between them and their return home. The imaginative surveyors saw an opportunity of getting home sooner rather than later by making up contours, and they chose the shape of an elephant!

Reflections

We were so thankful for Lee Rodrigues and the RGS facilitating our visit. It inspired many thoughts which we are still digesting. I share a few below.

It was exciting yet overwhelming to review primary material. In other research that I have undertaken, accessing such primary records was impractical. This activity of researching Fawcett made me aware of the finer details that are captured in the primary material while exposing me to the tremendous effort required just to read the handwriting!

Finding my expedition reports in the RGS’s archive and my description of a trek in the Bradt guide to Venezuela made me realize how such contributions stick around. Being able to access the Fawcett material highlighted the value of organizations having robust archives and staff that can catalog and look after historical artefacts.

The largest impact was the visit’s reignition of my desire to explore. Lee explained that the RGS’s definition of an expedition has changed over the last century. Having been aligned with the British Navy and their exploration of the British Empire before the Second World War, it has changed to focus on scientific discovery and working with local people. It is no longer about discovering lands like Fawcett did; his “discovery” was only from the perspective of the west, though Fawcett was invited by the Bolivian government to map the region. Dictionary definitions of expeditions centre around journey, purpose, discovery, and careful planning. When I organized university expeditions, I remember the emphasis placed on the importance of the expedition report, which I recognize thirty five years later. Expeditions take adventure and discovery up a notch though I apply many of these principles to all of my adventurous travels. Discovery might be my own or for the friends or family that accompany. Each trip is like a project or mini-expedition and our visit to the RGS was no exception. I identify a purpose, I plan, I execute, and then I write it up in this blog! Part of the goal is to help anyone who follows. This visit had made me want to increase my travel ambition. I thank the RGS for the support they provided in 1989 and for reigniting my expedition interest in 2025, and I thank Max for giving me the excuse to visit 1 Kensington Gore. If you are looking to get involved in expeditions, this RGS webpage is a great place to start.