TL;DR: An inspiring day visiting monasteries perched atop mountain peaks and surrounded by vertical cliffs. Their remoteness has helped their preservation through the centuries. On the way, we stopped by Leonidas’s statue at the site of the Battle of Thermopylae, the heroic fight between 300 Spartans and the Persian Army, as depicted in the movie, The 300. We were given three hours of free time before dinner, and an equally-crazy couple joined us to hike back up to a monastery, climbing 1,000 ft.

Thermopylae

The Greeks had beaten Darius I and his Persian army in 490 BC at Marathon to end the first Persian invasion attempt. Darius threw Daniel into the lions’ den (Daniel 6), and is mentioned as being supportive of rebuilding the Jerusalem Temple in Ezra 4:4-5. Xerxes I succeeded Darius and sought revenge against the Greeks, amassing an army of 120,000-300,000 soldiers. The Greeks had an army of 7,000 and chose Thermopylae to fight the invaders in 480 BC. There was a narrow pass which would greatly assist the defenders. Subsequent seismic activity and changing sea levels has significantly changed the local geology. The 7,000 Greeks were successfully holding the pass until a local Greek called Ephialtes showed the invaders a trail over the mountain that came out behind the Greek army. (Ephialtes now means “nightmare” in Greek, having previously just been a name). When General Leonidas learned of the treachery, he knew they would lose so allowed the army to retreat if they wished. However, along with 300 Spartan soldiers, he stayed and they fought to their death, killing a vast number of Persians. While the battle was not a victory, it contributed significantly to Greece’s decisive victory over the Persians the following year at the Battle of Plataea, ending the second Persian war. Xerxes returned to Susa after the defeat. Xerxes is the Greek name for the Aramaic name Ahasuerus, and it is possible that this is the same person as King Ahasuerus in Esther, with the events described in Esther occurring shortly after his return from Greece. Interestingly, Ahasuerus’s kingdom is described as from India to Cush (i.e. Ethiopia) omitting Greece (Esther 1:1). Note that this was the century before Alexander the Great, who took the throne of Macedonia in 336 BC and extended his empire eastward all the way to India, including Israel, Egypt, Assyrian, and Persia.

Meteora

As we traveled inland to Meteora, I was again surprised how mountainous Greece is. We headed deep into the mountains to some pinnacles with vertical cliffs. Meteora has evidence of monasteries dating back to the 11th century.

Monasticism’s roots go back to Egypt in the 4th Century. Rome’s acceptance of Christianity reduced the persecution of Christians but some felt this led to the diminishing of the quality of spiritual life. A man called Anthony lamented such degradation in his home city of Alexandria and found his way to live in desert caves around Mount Sinai. This led to the term “desert dweller,” eremos in Greek, which led to the English term “hermit.” The monastic movement spread throughout the Middle East and Asia Minor, and in the sixth century, inspired Benedictus, a church father from the western branch of the church, while visiting Constantinople (now Istanbul), leading to the formation of the oldest Catholic monastic order, the Benedictines. The word “monastery” represents being alone, from the Greek μόνος (monos).

In the 14th century, the Greek Athanasios (from Mount Athos) came to Meteora to establish a monastery. There may have already been some monks at the location since the 10th century. In 1312, the King of Serbia left his throne and joined Athanasios. They climbed the cliffs and started to build a monastery on the top. The location’s isolation and geography led to 24 monasteries built in this location. Many were destroyed by the Ottomans, others fell into disrepair, and six remain today (four for men, two for women).

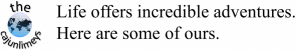

We visited the Monastery of Varlaam, which included a 145-step climb. Everything was neat and tidy, but the crowds meant the monks were a long way from being “alone.” We wondered what they felt about all of these tourists. The inside of the church was filled with paintings of icons – either biblical characters or saints. No photos allowed out of respect. There was a candelabra filled with oil in front of important icons. The pictures of saints were closer to the ground, as other humans can strive to be like them. Groups of icons were centered by one of Jesus, and there was a Jesus icon on the inside of the domes. Ceremonies such as baptisms and weddings take place directly below such icons of Jesus. Icons of Mary holding the baby often accompanied one of adult Jesus. The Greek Orthodox Church pray to Mary, as they believe Mary is between humans and Jesus, and Jesus does not say “no” to his mother (which sounded rather manipulative to us!) One icon depicted a monk praying over the bones of Alexander the Great, depicting that however “great” you are on this earth, only your bones remain on the earth. Another icon depicted God with a set of scales measuring how “good” a person was to decide whether someone should enter paradise. He shows grace to many that have been bad, but the worst join Satan and Judas in hell. It seems like a works-based salvation rather than completely about Jesus’s grace for those who accept Him.

Views of and from the monastery:

There were crowds of tourists

Marianne explained that the icons are similar to the pictures of their children that parents keep, but they do not worship them. Judaism banned such images so this influenced the early Christian church. By the fourth century, icons were appearing in the churches. At that time, when the Roman Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the empire in AD 381, he banned pagans religions leading to many pagans coming to the Christian churches but they worshipped the icons. The Byzantine Emperor Leo the Isurian recognized the prevalence of the pagan practice of worshipping icons and banned them in the 8th century, which is known as the “iconoclastic controversy.” However, icons were brought back into churches in the 9th century due to a lack of papyrus and the effectiveness of using images to teach about Jesus.

We also visited the monastery of St. Stephen. It was closed but we still got great views:

We stopped for lunch in town:

After lunch, we checked into our hotel and were told we had free time until dinner which gave us 3.5 hours free time. I made the most of the swimming pool and was again happy with my shoulders. We decided it was cool enough to go for a hike…

We went for a hike…

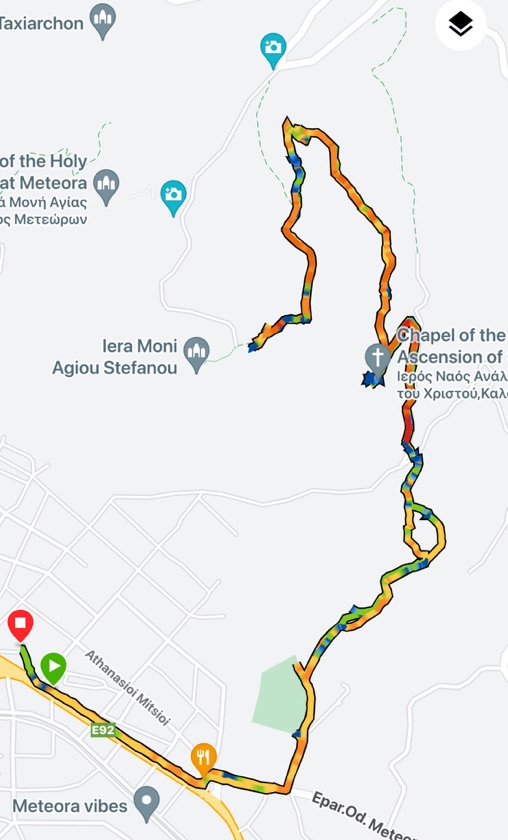

AllTrails showed a hiking trail going back up the mountain to the St Stephen’s monastery, starting close to our hotel. It had mixed reviews, was rated “moderate” difficulty, so was worth an attempt! 😎

It was less than two miles but 1000 ft of climb. Amber and Chad were crazy enough to join us for this “afternoon stroll.”

The following morning, we enjoyed views of the hotel and mountains in the dawn light.

Some final pictures of the mountains before leaving Meteora:

Reflection

The two visits so far have provided very interesting backgrounds on the periods that straddled Paul’s time in Greece. Delphi taught us so much about Ancient Greece, its mythology, and its history, supplemented by visiting Thermopylae, Leonidas’s statue, and learning about the Greco-Persian wars. Meteora taught us about the Greek Orthodox Church, the monasteries, and the differences between their church practices and what we experience in western evangelical Protestant churches. The Greek church have developed traditions with similarities to Roman Catholicism which differ from our interpretation of the Bible and the simplicity of access to Jesus and his grace. Marianne’s description of the church as the “temple” made me think of Judaism and the ornateness of the Jerusalem Temple. Her description of heaven as “paradise” sounded like Islam. However, she frequently tells us of her commitment to the Greek Orthodox faith. Her knowledge and perspective of the Greek language of the Greek New Testament has been most insightful. I look forward to what she will share at the locations we visit where Paul visited, which is imminent!