Luke describes Paul’s travels in Greece in Acts. Liberty University gave us the opportunity to follow in Paul’s footsteps with a couple of their learned professors, enabling us to get closer to appreciating Paul’s journeys. Details of the trip are on this page. Below I use my photos and text to describe what we saw that helped bring Paul alive, aligned with Luke’s account.

A map of Paul’s “Second Missionary Journey” from AD 50-52, Acts 15:22-18:23, from the ESV Bible Atlas by John D. Currid and David P. Barrett.

“From Troas we put out to sea and sailed straight for Samothrace, and the next day we went on to Neapolis.” (Acts 16:11, NIV)

“From there we traveled to Philippi” (Acts 16:12a)

“a Roman colony and the leading city of that district of Macedonia.” (Acts 16:12b)

“And we stayed there several days.” (Acts 16:12c)

“On the Sabbath we went outside the city gate to the river, where we expected to find a place of prayer. We sat down and began to speak to the women who had gathered there. One of those listening was a woman from the city of Thyatira named Lydia, a dealer in purple cloth. She was a worshiper of God. The Lord opened her heart to respond to Paul’s message. When she and the members of her household were baptized, she invited us to her home. ‘If you consider me a believer in the Lord,’ she said, ‘come and stay at my house.’ And she persuaded us.” (Acts 16:13-15)

“Once when we were going to the place of prayer, we were met by a female slave who had a spirit by which she predicted the future. She earned a great deal of money for her owners by fortune-telling. She followed Paul and the rest of us, shouting, ‘These men are servants of the Most High God, who are telling you the way to be saved.’ She kept this up for many days. Finally Paul became so annoyed that he turned around and said to the spirit, ‘In the name of Jesus Christ I command you to come out of her!’ At that moment the spirit left her.” (Acts 16:16-18)

A literal translation of Luke’s phrase “a spirit by which she predicted the future” is “a spirit of Python”.

The Greek text clearly references “python” but translators have decided this would confuse readers. During the first century AD in Greece, the spirit of Python would have been associated with the Oracle of Delphi who predicted the future. In Greek mythology, a python guarded the Oracle until Apollo killed it.

The next “we” passage is not until Acts 20:4, when Paul returns to Philippi, suggesting that Luke did not travel with Paul during this time.

“When her owners realized that their hope of making money was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace to face the authorities. They brought them before the magistrates and said, ‘These men are Jews, and are throwing our city into an uproar by advocating customs unlawful for us Romans to accept or practice.'” (Acts 16:19-21)

Timothy and Luke, who accompanied Paul, were not ethnic Jews so avoided the accusation and punishment.

“The crowd joined in the attack against Paul and Silas, and the magistrates ordered them to be stripped and beaten with rods.” (Acts 16:22)

“After they had been severely flogged, they were thrown into prison, and the jailer was commanded to guard them carefully. When he received these orders, he put them in the inner cell and fastened their feet in the stocks.” (Acts 16:23-24)

“About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the other prisoners were listening to them. Suddenly there was such a violent earthquake that the foundations of the prison were shaken. At once all the prison doors flew open, and everyone’s chains came loose. The jailer woke up, and when he saw the prison doors open, he drew his sword and was about to kill himself because he thought the prisoners had escaped. But Paul shouted, ‘Don’t harm yourself! We are all here!'” (Acts 16:25-28)

“The jailer called for lights, rushed in and fell trembling before Paul and Silas. He then brought them out and asked, “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” They replied, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved—you and your household.” Then they spoke the word of the Lord to him and to all the others in his house. At that hour of the night the jailer took them and washed their wounds; then immediately he and all his household were baptized. The jailer brought them into his house and set a meal before them; he was filled with joy because he had come to believe in God—he and his whole household. When it was daylight, the magistrates sent their officers to the jailer with the order: “Release those men.” The jailer told Paul, “The magistrates have ordered that you and Silas be released. Now you can leave. Go in peace.” But Paul said to the officers: “They beat us publicly without a trial, even though we are Roman citizens, and threw us into prison. And now do they want to get rid of us quietly? No! Let them come themselves and escort us out.” The officers reported this to the magistrates, and when they heard that Paul and Silas were Roman citizens, they were alarmed. They came to appease them and escorted them from the prison, requesting them to leave the city. After Paul and Silas came out of the prison, they went to Lydia’s house, where they met with the brothers and sisters and encouraged them. Then they left.” (Acts 16:29-40)

“When Paul and his companions had passed through Amphipolis and Apollonia, they came to Thessalonica, where there was a Jewish synagogue. As was his custom, Paul went into the synagogue, and on three Sabbath days he reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving that the Messiah had to suffer and rise from the dead. “This Jesus I am proclaiming to you is the Messiah,” he said. Some of the Jews were persuaded and joined Paul and Silas, as did a large number of God-fearing Greeks and quite a few prominent women.” (Acts 17:1-4)

“But other Jews were jealous; so they rounded up some bad characters from the marketplace, formed a mob and started a riot in the city. They rushed to Jason’s house in search of Paul and Silas in order to bring them out to the crowd. But when they did not find them, they dragged Jason and some other believers before the city officials, shouting: “These men who have caused trouble all over the world have now come here, and Jason has welcomed them into his house. They are all defying Caesar’s decrees, saying that there is another king, one called Jesus.” When they heard this, the crowd and the city officials were thrown into turmoil.” (Acts 17:5-8)

“Then they made Jason and the others post bond and let them go.” (Acts 17:9)

At times, we were frustrated by the traffic, or the bus we travelled on, or the length of time to get between these sites. Our visit reminded us that Paul was travelling on foot between these sites while recovering from nearly being beaten to death.

Perhaps Paul had planned to continue travelling westward along the Via Egnatia to Rome, but something prevented him (Romans 1:13). Berea was also a logical location for Paul to visit while waiting to see what happened with the tensions in Thessaloniki as Berea had a synagogue. Perhaps Paul was too badly injured to travel far.

“As soon as it was night, the believers sent Paul and Silas away to Berea. On arriving there, they went to the Jewish synagogue. Now the Berean Jews were of more noble character than those in Thessalonica, for they received the message with great eagerness and examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true. As a result, many of them believed,” (Acts 17:10-12a)

“as did also a number of prominent Greek women and many Greek men.” (Acts 17:12b)

“But when the Jews in Thessalonica learned that Paul was preaching the word of God at Berea, some of them went there too, agitating the crowds and stirring them up. The believers immediately sent Paul to the coast, but Silas and Timothy stayed at Berea. Those who escorted Paul brought him to Athens and then left with instructions for Silas and Timothy to join him as soon as possible.” (Acts 17:13-15)

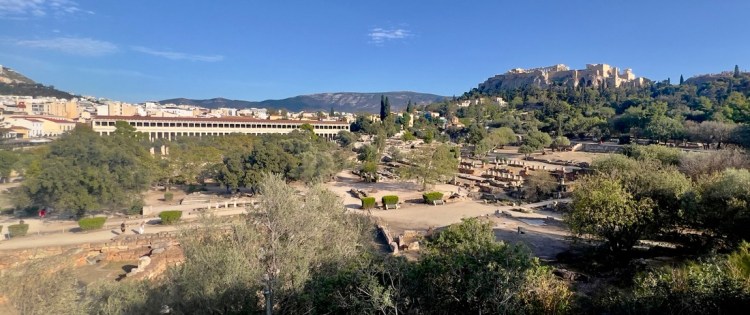

“While Paul was waiting for them in Athens, he was greatly distressed to see that the city was full of idols.” (Acts 17:16)

“So he reasoned in the synagogue with both Jews and God-fearing Greeks, as well as in the marketplace day by day with those who happened to be there.” (Acts 17:17)

“A group of Epicurean and Stoic philosophers began to debate with him. Some of them asked, “What is this babbler trying to say?” Others remarked, “He seems to be advocating foreign gods.” They said this because Paul was preaching the good news about Jesus and the resurrection. Then they took him and brought him to a meeting of the Areopagus, where they said to him, “May we know what this new teaching is that you are presenting? You are bringing some strange ideas to our ears, and we would like to know what they mean.” (All the Athenians and the foreigners who lived there spent their time doing nothing but talking about and listening to the latest ideas.)” (Acts 17:18-21)

“Paul then stood up in the meeting of the Areopagus and said: “People of Athens! I see that in every way you are very religious. For as I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: to an unknown god. So you are ignorant of the very thing you worship—and this is what I am going to proclaim to you. “The God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands. And he is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything. Rather, he himself gives everyone life and breath and everything else. From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands. God did this so that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us. ‘For in him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring.’ “Therefore since we are God’s offspring, we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent. For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead.” When they heard about the resurrection of the dead, some of them sneered, but others said, “We want to hear you again on this subject.” At that, Paul left the Council.” (Acts 17:22-33)

“Some of the people became followers of Paul and believed. Among them was Dionysius, a member of the Areopagus, also a woman named Damaris, and a number of others.” (Acts 17:34)

“After this, Paul left Athens and went to Corinth. There he met a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, who had recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had ordered all Jews to leave Rome. Paul went to see them, and because he was a tentmaker as they were, he stayed and worked with them.” (Acts 18:1-3)

“Every Sabbath he reasoned in the synagogue, trying to persuade Jews and Greeks. When Silas and Timothy came from Macedonia, Paul devoted himself exclusively to preaching, testifying to the Jews that Jesus was the Messiah. But when they opposed Paul and became abusive, he shook out his clothes in protest and said to them, “Your blood be on your own heads! I am innocent of it. From now on I will go to the Gentiles.” Then Paul left the synagogue and went next door to the house of Titius Justus, a worshiper of God. Crispus, the synagogue leader, and his entire household believed in the Lord; and many of the Corinthians who heard Paul believed and were baptized. One night the Lord spoke to Paul in a vision: “Do not be afraid; keep on speaking, do not be silent. For I am with you, and no one is going to attack and harm you, because I have many people in this city.” So Paul stayed in Corinth for a year and a half, teaching them the word of God.” (Acts 18:4-11)

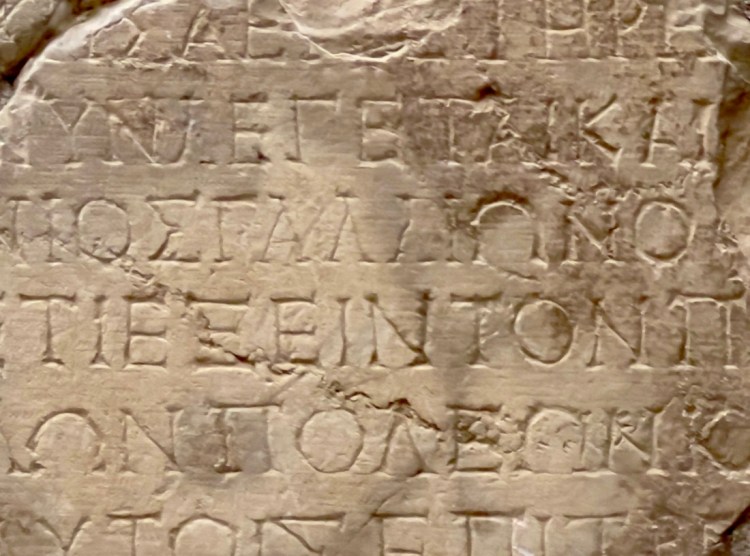

“While Gallio was proconsul of Achaia,” (Acts 18:12a)

Delphi is located by the “c” in the middle of the word “Cenchreae.”

“the Jews of Corinth made a united attack on Paul and brought him to the place of judgment. “This man,” they charged, “is persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law.” Just as Paul was about to speak, Gallio said to them, “If you Jews were making a complaint about some misdemeanor or serious crime, it would be reasonable for me to listen to you. But since it involves questions about words and names and your own law—settle the matter yourselves. I will not be a judge of such things.” So he drove them off. Then the crowd there turned on Sosthenes the synagogue leader and beat him in front of the proconsul; and Gallio showed no concern whatever.” (Acts 18:12b-17)

Gallio’s dismissal of the Jews’ complaint shows that Rome, at this time, treated Christianity as a Jewish sect, and differences between these sects was not a Roman problem.

“Paul stayed on in Corinth for some time. Then he left the brothers and sisters and sailed for Syria, accompanied by Priscilla and Aquila. Before he sailed, he had his hair cut off at Cenchreae because of a vow he had taken.” (Acts 18:18)

Paul leaves Greece for a few years. In his second letter to the Corinthians, which he wrote from Ephesus, Paul indicates he made a painful visit (2 Cor 2:1).

Luke describes Paul’s return to Greece, without much detail, in Acts 20:

“When the uproar had ended, Paul sent for the disciples and, after encouraging them, said goodbye and set out for Macedonia. He traveled through that area, speaking many words of encouragement to the people, and finally arrived in Greece, where he stayed three months. Because some Jews had plotted against him just as he was about to sail for Syria, he decided to go back through Macedonia. He was accompanied by Sopater son of Pyrrhus from Berea, Aristarchus and Secundus from Thessalonica, Gaius from Derbe, Timothy also, and Tychicus and Trophimus from the province of Asia. These men went on ahead and waited for us at Troas. But we sailed from Philippi after the Festival of Unleavened Bread, and five days later joined the others at Troas, where we stayed seven days.”(Acts 20:1-6)

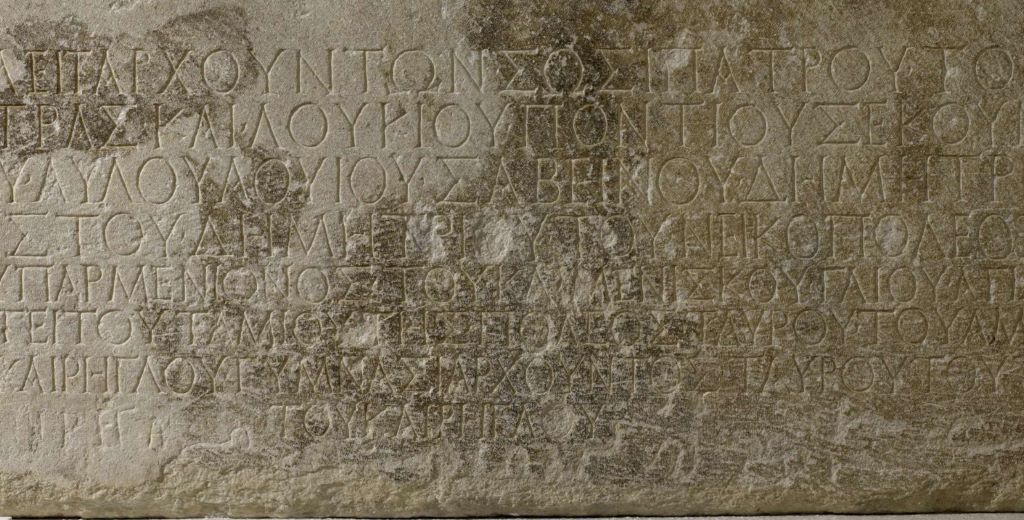

In the picture, Dr Laird explains the significance of this inscription, one of three significant ones (the others being the Delphi Inscription and the Politarch Inscription.

In the picture’s background is Acrocorinth. While the ancient author Strabo claimed that the Temple of Aphrodite was located on the top of Acrocorinth, the significance of this temple is disputed by some modern scholars.

Extra Bits

An understanding of ancient Greece is essential to understand the environment in which Paul travelled, and the context in which he wrote his letters. Visits to ancient temple sites in Delphi and Athens helped us understand this background. Visits to Thermopylae and Philip’s tomb at Vergina helped understand Greece’s history around Alexander the Great. The visits were supplemented with great guides and good guidebooks, especially Costas Tsevas work in which he provides insights from ancient Greek culture to bring the New Testament alive.

Our visits also provided fascinating insight into more recent Greek history. Visits to monasteries and churches helped us begin to understand the Greek Orthodox Church, which 98% of Greek’s attest to being a part of. Greece’s struggle with Turkey during the Ottoman rule from the fifteenth century and its successful fight for independence in 1821 drives a Greek pride, seen in the plethora of Greek flags. Perhaps the presence of churches everywhere, even in the most remote and inhospitable parts of the country, is driven by the Greek’s desire to continuously state that they are Christian Greeks, not Muslim Turks.

Finally, the group brought fresh perspectives on many topics through its diversity. Everyone in the group was either student, graduated student, professor, or spouse. The twenty-seven participants represented six countries (USA, UK, South Korea, South Africa, Philippines, and Venezuela), testifying to the ability to complete the PhD remotely. There was an even split of people travelling as couples or by themselves. Professions ranged from pastors and chaplains to combat-hardened soldiers, from professors and teachers to a business owner, a retired engineer, and an OB/GYN. Multiple denominations were represented. The common interest in understanding more about the Bible defined the group as we followed in Paul’s footsteps.

Read the blogs from each day here.

This must have been amazing.

LikeLike